For students at Santa Rosa’s Anova Center for Education, the month since the devastating North Bay Fires has been really tough. The school serves high-functioning kids on the autism spectrum. They tend to be anxious and have trouble adapting to change. But their school burned down. And nine families lost their houses, too. Coping — and getting back to a calming routine — has been challenging.

Unsettled

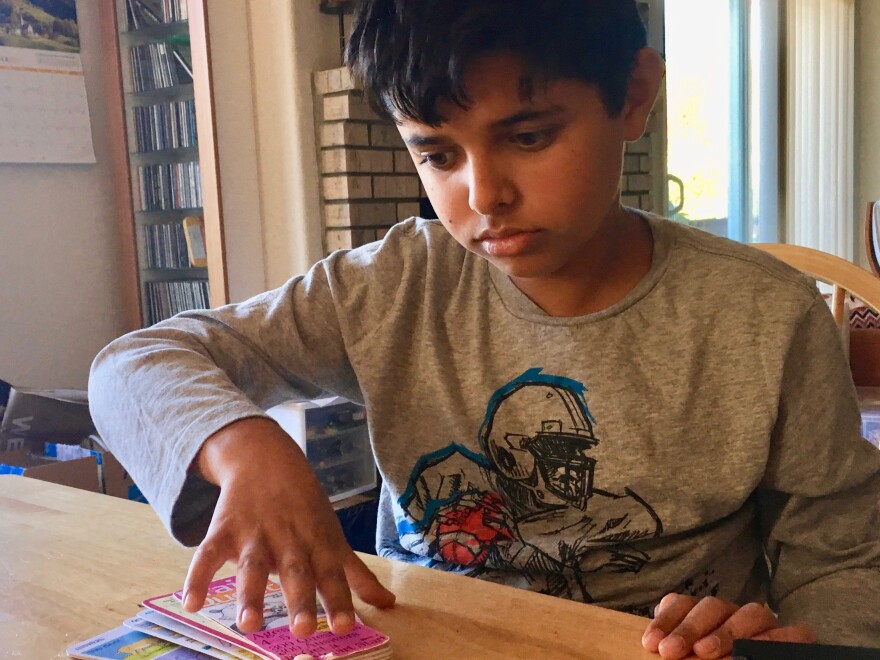

Jaco Sodhi and his twin sister will celebrate their twelfth birthday this month. It should be a happy time. But their lives are upside down.

When I meet the kids and their parents, they’re staying at the Santa Rosa home of family friends — the fourth place they’ve landed since the North Bay fires started.

Jaco sits down at the piano, and his dad, Raj Sodhi, helps him work through a piece of music. It helps them feel a little bit normal.

The family had to evacuate their own home not far from here in the early hours of October 9. Jaco’s dad, who plays jazz, loaded his double bass into the family minivan. His mom, Lucia Cascio, a portrait photographer, grabbed her camera bag. And his sister, Sofia, managed to take her trombone.

But Jaco ran out of time. He left without much besides his Star Wars shirt — the one that’s got Darth Vader on it playing baseball with a light saber. He says it all happened too fast.

“My sister said, ‘We are evacuating, Jaco, just get out of your dang bed — yeah my sister was cruel that way — and I was able to grab, literally my toothbrush, toothpaste and only one pair of clothes.”

Jaco’s pretty unhappy about that. The family thought they were just being cautious, that they’d be able to return soon. But their house, and everything in it, burned down.

“If I could have grabbed more,” Jaco says, “I probably would have grabbed all my fencing gear, which costs like hundreds of dollars.”

Jaco’s got big brown eyes, braces and a very rational mind. He was diagnosed with autism when he was three-and-a-half years old. Kids on the autism spectrum don’t do well with big changes — and a lot is up in the air for him right now.

He puts on a good face, but he’s clearly struggling with his feelings. He talks about riding an imaginary lion into his devastated neighborhood — to chase off looters. And he tells his mom — three times — how mad he is “that I was able to grab, basically nothing.”

Without a house, his parents have even been talking about leaving

Sonoma County. Because Jaco’s school? It burned too.

“Yeah, it was pretty sad,” he says about the moment he learned that his classroom, his locker — even the pile of soft fur he’d amassed from his dog, a shiba inu with fat cheeks — were “actually gone.”

Then his logical self takes over. The loss is sort of predictable, he explains, because the building’s wood supports and banisters likely caught fire, and then the carpets, and “that’s gonna spread all around to all the other classrooms.”

Transformation

To understand just how hard this is, it helps to know what things were

like for Jaco before Anova. He spent kindergarten, first and second grades at a public school, but he struggled.

Cascio, his mom, says there were instances when Jaco was aggressive with his peers, “pulling down the shelves in the library where they were trying to keep him away from the other kids, and it was just getting worse and worse.”

The whole time, she and her husband were pushing to find the right classroom environment and behavior plan for him at his public school, but Jaco started having suicidal thoughts.

And his outbursts were regular.

Cascio was working part-time, so she was the one who often got the call from the school that something was wrong. Her stomach sank whenever she saw the number pop up on her caller ID.

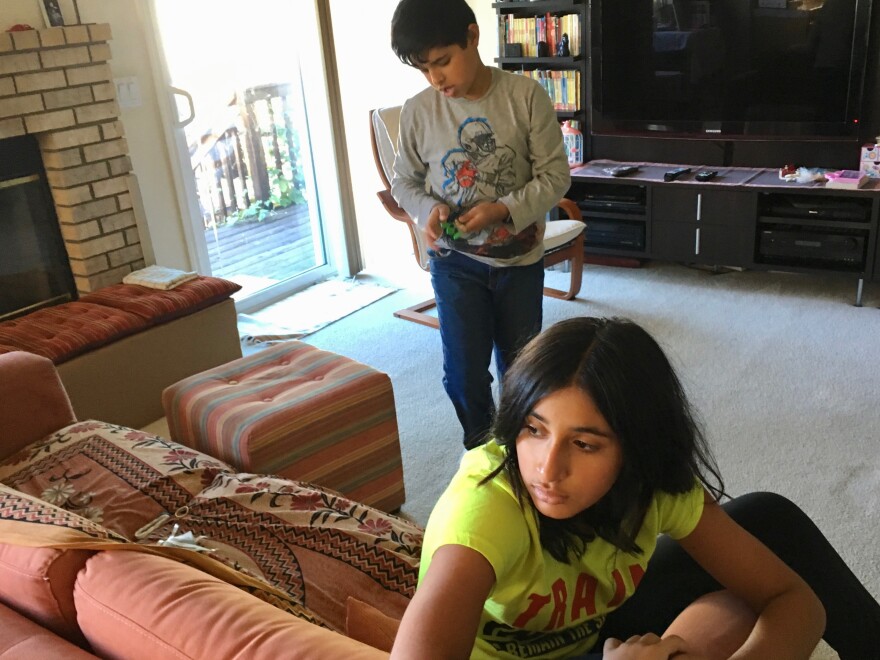

It was tough for Sofia, Jaco’s sister, to see how misunderstood her brother was.

In the years after he left for Anova, kids would approach her, “not as Sofia but, like, ‘You’re Jaco’s sister,” she says. “‘You’re the one who’s related to the guy that pulled my hair’ or something. It’s like: No! He’s Jaco. He’s not just a hair puller. He can learn stuff.”

When Jaco finally got to Anova, everything changed. He speaks softly when he talks about it, gazing down at the table. It’s clearly painful.

“They weren’t treating me as if I was a bad person,” he says, “for like the first time in a while ... It hasn’t happened in a while for me.”

Anova’s students come from as far as 80 miles away. Like Jaco, most are

referred by their public school districts, which cover the costs. When Jaco got in, he skipped a grade. And his outbursts? They dwindled to almost nothing.

The kids can leave class whenever they need a break. There are quiet rooms for calming down, rooms where they can jump on a trampoline or swing, to help them feel more connected to their bodies. Plus counselors to talk to — and there’s a therapy dog, named Larry.

Jaco loves his Larry breaks. Sometimes, he grabs some of Larry’s toys and plays with him. He gives him belly rubs. And he likes to “just flop his ears around.”

“Most of the time he just sleeps on his bed,” Jaco adds, “which hopefully

wasn’t, which probably might have been burned in the fire.” He pauses. “Hopefully wasn’t.”

Fear of Moving

Jaco’s dad was so worried about not being able to find housing in

Sonoma County, he already took Jaco to check out two other schools for kids with autism -- in distant communities where they might have better luck. Jaco says “necessity beats friends” so he’ll go if he has to. But the upheaval is taking a toll.

Cascio said Jaco was “really low and sad” after those tours, “and you know, the thought of changing was probably heavy for him.”

Jaco interrupts her to make it clear that he really doesn’t want to change schools. She tries to soothe him.

“We’re trying really hard to stay here, right?” she says. “That’s what mommy and daddy are trying really hard to do.” It seems to help.

“Got it,” Jaco says. “That’s what I was just waiting to hear, that we’re actually trying to stay and we’re not just trying to move away.”

Anova scrambles for space

About a week after the fires started, families piled into the Odd Fellows

Hall in Santa Rosa to get an update from Anova’s chief executive.

There are snacks and books and puzzles and a painting station in the lobby. Inside the hall, Andrew Bailey quiets the crowd to tell them school will be back in session soon. And that none of them have been forgotten in the chaos.

“The number one thing that we have been talking about since day one is how are these kids, how are these families, who lost a home,

who needs help? Who’s at risk of leaving the county?” he says, telling families who’ve lost homes to reach out to staff with their needs.

“We’re trying to keep people here. We don’t want anybody to have to

leave.”

Parents hold signs thanking the school staff. Some sport “Anova Strong” shirts they designed the day before. There’s a lot of applause, a lot of appreciation.

Bailey is Anova’s CEO and director of educational services. He also co-founded the school 17 years ago. He was a therapist back then. And he realized that these high-functioning kids with autism, the ones that often test at grade level, were falling through the cracks.

“All of us really started understanding that the students like the ones we serve are not misbehaving because they're bad or manipulative, and that is a game-changer for our students,” he says in an interview at the school’s administrative offices, which didn’t burn. “They're understood and they're addressed with sensory sensitivity.”

Bailey knows that sensitivity will be more important than ever when

school reopens.

“They do understand the dangers in life,” he says, so when something like a fire comes along, the stresses in the students’ lives become exacerbated.

Anova’s therapists know all that, and when school gets back in session, Bailey says, they’ll be ready to help students like Jaco assess how they’re feeling and calm down using techniques such as "breathing and imagination and rationalization.”

The charred campus

Bailey and I decide to take a drive to the charred campus, about three miles away. He takes a route that’s just been reopened to traffic. A view of burnt hills in the distance gives way to blackened neighborhoods that stretch for blocks. He hasn’t seen this devastation yet.

“That was a community of homes right there,” he points, “and right there.”

When we get to the campus, in space provided by the adjoining Luther Burbank Center — which survived relatively unscathed — the lawn is still vibrant green.

A couple of baked tomatoes cling to a surviving vine in what was once the the small school garden. But other than a few rooms on the far end, the building is a cinder block shell filled with wreckage.

Bailey takes a photo of the blistered tomatoes. Then it’s time to go.

“I’ve seen enough for today,” he sighs. “I can’t take it anymore. I like what we’re doing to build better than looking at that. That’s hard.”

Back at Anova’s administrative offices, Bailey’s mood lifts. A suite of

rooms are buzzing with teachers and therapists finishing lesson plans and

ordering supplies.

Anova will fit some students here, broken up into smaller classrooms than usual. The rest will be split between two other schools in the county with classrooms to spare. In the New Year, Anova expects to set up portable classrooms at its old location and await a full rebuild.

For now, the school’s team of therapists will split up too, so each site will be

staffed all day. The only rover will be Larry, the golden retriever labrador

mix. He’ll make his rounds with Principal Heidi Adler. And yes, his bed did burn. But he seems to be doing ok. He sits on his hind legs and gives Bailey a hug. Then, on command, he speaks and executes a perfect twirl.

School starts

Classes are back in session by the following Monday. It’s a warm day at the end of October. Jaco’s class and two others are in borrowed space

in Healdsburg for now. The head counselor spent the morning talking to

students about what they’ve been through. Now they’re making art.

A few kids listen to music on headphones. One hums. Another takes a break on a sofa. A third is hunched over his desk, curled into his hoodie. The teacher, Alicia Honn, steers him outside for a break.

Jaco sits near the front of the classroom, drawing a picture of a shiba inu. His dog, Akira, has been staying with a pet sitter and Jaco really misses her.

There’s good news though: His family found rental housing through a friend — in Healdsburg, just a couple of miles from here.

Sofia, Jaco explains, “feels that it’s the stupidest place we could possibly get a house.” She really wants to stay closer to her friends, but Jaco says “all that matters is that we at least have one.”

Anova staff tried to replicate the students’ old classroom as much as possible, down to the posters on the wall and the type of box that holds the headphones. All the Chromebooks and textbooks, every single pencil and paper folder, everything had to be replaced.

Outside, the kids mill around in the unfamiliar parking lot, waiting for a ride home. The new space, says Honn, is an adjustment.

“We had more tables in the back so they could spread out, and a nice library, and the nook in the back with big bean-bag chairs,” she says.

But for these kids with autism, just getting back to routine is a huge

relief.

“You could just feel the positivity from all of them, just seeing their friends and seeing their teachers,” she says, “and just being like, ‘ahhhhhh, normalcy.’”

That’s even true for Jaco. As Honn talks, he sits on the ground in the shade next to a friend. They play together with a handheld video game, laughing.

Anova’s counselors will be tracking the kids closely as they heal, looking for atypical behaviors, sadness, and anger. It’s going to take some time.

Asked what score he’d give the new space on a scale from one to ten, Jaco says he’d give it a five, “just because I want to.”

As he speaks, a boy nearby shouts, over and over, “fire hazard, fire hazard, fire emergency!”

For now, it seems, the the fire still looms large.