Shortly after Alcatraz prison shut down in 1963, the people who lived and worked on the island began hosting annual get-togethers. When the National Park Service invited the “alumni” to host the reunions on the island, convicts were invited, too. This year, as surviving alumni dwindle, the tradition is coming to an end.

The final Alcatraz Alumni Reunion is in full swing, and the alumni are eating biscuits and drinking coffee inside the old prison. There are about forty alumni, mostly kids and grandkids of old prison employees and others who lived on the island. They share memories growing up on the Rock and stories about the prison. The prison is a strange backdrop to all this light-hearted fun.

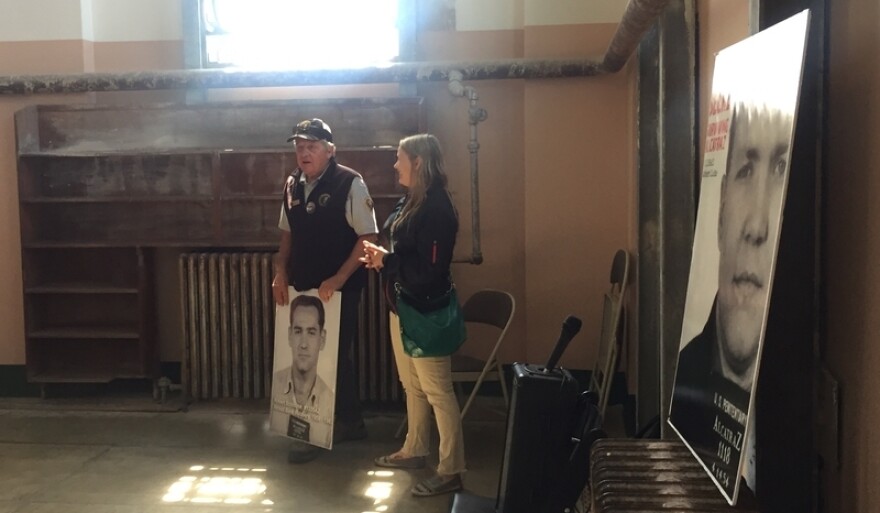

In a room down below, tourists gather round for an event called Call-a-Con. As the name suggests, a former Alcatraz inmate phones in. Robert Schibline, an 87-year-old ex-bank robber, calls in from his home in Florida. A park ranger waves his mug shot for the audience, declaring for the crowd, “He’s a pretty handsome guy, don’t you think?”

The con’s stepdaughter, Kelly Rabe, beams with pride from the front row.

Her dad has a captive audience. He talks all about his theories about the prison escapees (he says he supplied them with tide tables but doesn’t believe they survived the ocean). He describes the prison menu (pork chops, fresh fish, t-bone steaks) and talks about spending time in the hole (a pitch black, soundproofed solitary confinement cell). When the talk is over, the crowd applauds him, like he’s a hero.

Former cons willing to talk are rare. Of the forty Alcatraz alumni here, most are kids and grandkids of former Alcatraz prison employees. But at the Alcatraz Alumni Reunion, being an ex-convict makes Schibline a star. For most of his life, though, Schibline kept quiet about his time on Alcatraz, only telling people he could trust.

The Enforcer

Schibline says he was brought to the federal penitentiary in 1958 for his role in a food strike at Leavenworth, a federal prison in Kansas. He still remembers getting out of the boat to Alcatraz, and seeing the island drowned in fog for the first time. He thought about all the infamous criminals who served time there, from Machine Gun Kelly to the Birdman of Alcatraz to Al Capone. By then, Alcatraz had been open for over two decades as a federal prison. It had already garnered a reputation as one of the most notorious prisons in the country.

"You only got sent to Alcatraz if you were malcontent, a troublemaker, an escape risk, or if you were a piece of sh*t," Schibline says. "I was probably two or three of those things."

Before Schibline was sent to Alcatraz, he served time at Leavenworth for robbing banks while he was still in the Navy. People at Leavenworth called him “the Enforcer” because he could intimidate anyone. He says he taught other inmates martial art techniques designed to kill people. But once at Alcatraz, he remembers thinking, “There are maybe two hundred people here who think they’re the Enforcer too”.

So he kept to himself. Inmates at Alcatraz were kept in single cells and rarely allowed to leave, except for meals. There were no calendars or clocks, and, Schibline says, the days and the years rolled together in a monotonous jumble. After five years, he served his time and was released.

Schibline never went back to robbing banks. Instead, he opened a scuba diving shop and taught people how to scuba dive until he retired. He got married. He told his wife he served time on Alcatraz on their third date, and she told him she was just happy he wasn’t a rapist. For the most part, though, he never mentioned Alcatraz again.

But he never forgot how the cell doors sounded when they slammed shut. He vowed never to lock a door again when he got out, and he’s kept that promise. His door, he says, is always unlocked. Other than that, he left his bank-robbing days and his time on Alcatraz behind him.

That is, until his step daughter, Kelly Rabe, began researching Alcatraz for a college project.

A rock star on a trip to Alcatraz

In 2004, Rabe found out about an annual get-together called the Alcatraz Alumni Reunions. When Rabe told the National Park Service her stepdad was still alive, they asked him to come to the island and speak.

“I found out they had the reunions, and I was like, ‘Oh my god, we have to go!’” Rabe remembers. “So as a Christmas gift, I purchased a plane ticket for him and my mom to come out here. That way he had no choice but to come.”

So the family arrived for the 2005 Alcatraz Alumni Reunion. Now Rabe is an Alcatraz history buff, and proud of her stepdad’s role in that history. There is only one other convict who talks at this most recent reunion “Some people are like distant relatives, but I actually grew up with a con, so I feel pretty special,” Rabe says. “His number is 1355. Google it.”

Her stepdad couldn’t make it to this most recent reunion. When he did come to the reunion in 2005, though, he was terrified about how the tourists would treat them. He expected angry tourists and jeers. Instead, he says, it was like he couldn’t do any wrong. They pushed his wife and daughter out of the way to get a picture with him. “I was amazed at the treatment I got at Alcatraz,” Schibline says, referring to his comeback. “They treated me with all the respect of a rock star.”

Now Rabe is happy to hear her step dad open up about what it was like on the island. “All this time, he had to hold it in, and so he didn't really talk about it,” she says. “But now, here he is, and everybody wanted to talk to him. He was just excited to answer questions and talk.”

At this event, Rabe even hands out her stepdad’s autographs, and copies of a DVD with the Alcatraz Alumni Reunion of 2005. Schibline says he gets roughly five hundred letters a year from people who want to hear about Alcatraz. He even mails his “fans” Alcatraz memorabilia.

“Bars of soap, dining tray, tin cup, the escape spoon, name tags, I've got all that stuff here,” says Schibline. “If people want a souvenir, I can give them whatever they want. I even got a keychain that has a pair of handcuffs that actually open up and close. I give them to my fans.”

How the myth of Alcatraz was born

Alcatraz is the most loved landmark in America, so says TripAdvisor. On the international version of the list, it ranks number eight, beating out the Eiffel Tower and Greece’s Acropolis. The allure of Alcatraz and its prisoners goes way back.

John Martini, a retired National Park park ranger and Alcatraz historian, says he used to give tour guides on the Rock. He remembers he once told tourists, “Welcome to the rock where every convict was a killer waiting to be executed, where the gas chamber ran 24 hours a day, where the guards were the most sadistic in the system.”

Then he paused, and said, “Everything I've just told you is a lie. That's not Alcatraz. We're going to discover the real Alcatraz.”

Martini says Alcatraz is thought to be the place where the “worst of the worst” end up. But it’s more complicated than that. People who escaped from other prisons, or started riots, were sent there. The government used Alcatraz as a threat to deter wannabe criminals and prison escape artists when it opened up in 1934. The first few years the prison opened, inmates weren’t allowed to talk, except in the recreational yard.

"They wanted it to be a deterrent. They wanted it to be this is Uncle Sam's answer to organized crime and gang war bosses," Martini says. "The poster boy was going to be Al Capone, but you also had people convicted of much more minor crimes."

Hollywood, he says, bought it too, hook, line, and sinker.

“People come in there with real preconceived ideas based on media,” says Martini, “especially after seeing things like — God help us — The Rock, or Escape from Alcatraz, or the Birdman of Alcatraz.”.

After the prison closed down, Martini interviewed inmates, guards, and prison staff. He says that from those oral histories, he learned the food on Alcatraz was pretty good, the guards ran a tight ship, and fights and gangs at the jail were rare. But out at sea, inmates still felt isolated.

“Most of them will grudgingly admit that although it was no fun place to spend time it was a lot better than a lot of other institutions they'd been in,” Martini says. “There were one-man cells, not a lot of gang activity. But for the most guys, it was a relief after coming from really overcrowded prisons. On Alcatraz, you were constantly being watched.”

Alcatraz: the postcard of small-town USA

The alumni here for the reunion are mostly former residents and their offspring. They yearn for a simpler time in their lives, a world away from crime.

Bill Hart is the grandson of a former Alcatraz prison guard. “My dad always said he liked living on the island. He felt really safe there. He said, ‘Nobody, nobody that lived there even had a key, they never locked their doors. They knew everybody. Grandma always said, all the kooks are locked up.”

People here joke that Alcatraz was the country’s first true gated community. Their eyes glisten when they talk about life on the island.

As Kathe Kaeppel Poteet, daughter of the island’s chief financial officer, recalls growing up on Alcatraz, it sounds like she talking about a postcard image of small-town U.S.A.

“We had lots of things going on there, we had pot lucks, we had parties, the bowling alley was down below, we had a couple of playgrounds, all different kinds of friends, roller skating, the whole bit,” Kaeppel Poteet remembers.”It was a small town, everybody knew everybody else. It was fun, a lot of fun."

But life was not so simple on the island for the residents. They had to follow strict rules and protocols concerning the prisoners.

Carol Blum’s sister married a guard at the prison. She still remembers what visiting Alcatraz was like. “You'd get off the boat and all of the prisoners that were working on the docks will have to move back and stand behind yellow lines,” Blum says. “They were not allowed to speak to us and really they didn't even want them looking at us.”

The residents would catch sharks, and leave them on the rocks for the inmates to see in an effort to deter them from trying to escape. Inmates did laundry for the residents and even crafted their furniture. Not everyone was comfortable with that proximity.

“I mean, it wasn't an easy life. You can have the inmates do your laundry, but my mom's like, ‘I don't want them touching my laundry’,” Becky Walker Fagernes, who lived on Alcatraz with her family, remembers.

In 1964, the year after the prison shut down, residents organized reunions like the one in parks and campsites around California to keep the memories alive.

Walker Fagernes was the last child born on Alcatraz. She was too young to have any full memories of what it was like to grow up on the island. The reunions have given her an opportunity to find out more about her family's history. She says she’s found a community at the reunions.

“I feel like I'm an adopted child,” says Fagernes. “I've found my family and I'm learning all the history.”

Ex-cons and the former guards make peace

Decades after the island closed, the alumni began hosting their reunions on the island. Park Ranger John Cantwell says the National Park Service invited the inmates to the reunion. They wanted to represent all sides of the Alcatraz story.

"Who better to tell the story than somebody that was up in a guard tower or locked up in a jail cell?" Cantell says. "That's the reason why we've done this."

Since then, ex-cons and former guards have posed for photos together, and even had sleep-overs in jail cells.

Cantell tells a story about having dinner with a Phil Bergen, the former Captain of the Guard, and an ex-convict, Leon Thompson.

“I'll never forget leaning over to Phil and asking him his opinion of this old convict,” says Cantell. “He looked at me, he said, ‘he's paid his debt to society and I treat him as an equal.’”

Cantwell explains that the alumni reunions have acted as a healing process. The convicts get to come to back and face the former guards and prison as free men.

“I have always kind of equated it to the civil war guard meetings,” says Cantwell. “The old confederacy and union soldiers would get together and have a campout. And now they’re gathering as friends and survivors.”

Defining people by their punishment

Because of the mythology behind Alcatraz, former cons are able to reach celebrity status.

It can feel surreal to hear a stepdaughter and her father boost about being incarcerated, even if it is at Alcatraz. We’re often told not to define people by their crimes. But here, ex-cons are defined by both the crime and by the punishment—as celebrities and heroes.

But the people who did the punishment — or at least helped enforce the rules — are here at the reunion too. Two former guards are here. The tourists keep coming back for the stories of gangsters and escapees.

The tourists eat it up

This meeting of old-foes-turned-friends is exactly what the public wants to see. Both the Park Service and the media know it. At one point, during the alumni gathering, a park ranger whispers to come and follow her.

“We're creating an artificial moment here, where the guard is going to shake the inmates' hands,” the park ranger tells us.

Reporters from different media outlets are crowded into an old medical room. They snap photos while Bill Baker, an ex-con, and a former guard, Jim Albright, shake hands. Baker isn’t bitter.

“This guy, he did time like me, sort of like me. If you think about it, we both did many many hours, thinking about things,” Baker explains.

A dark kind of reunion

These reunions almost make incarceration seem like a good public relations move. But Bob Schibline, the ex-bank robber who served time at Alcatraz, says he refuses to shake hands with ex-guards here. One guard, he says, tried to shake his hand when he went to the reunion.

"Fifty years may have dulled your memory, but it hasn't dulled mine," he remembers telling the guard.

Schibline says he was put in solitary confinement in what was called “The Hole” and one guard would blow cigarette smoke in just for spite.

Schibline says that because of his treatment there, he drinks from a bottle of cognac every time a former guard dies.

Not all ex-cons return

But Cantwell says not all former inmates are willing or able to come back. One former convict, Cantwell recalls, named Armando Mendoza, vowed never to come back.

“He came out and talked about Alcatraz with the public and really wasn't happy to be here,” Cantwell says. “And as he left he said, this'll be the last time that I come back to this cesspool.”

Other convicts, even after getting out, went on to commit terrible crimes. Some others are still serving life sentences. Cantwell remembers he once invited a former inmate named Frank to the reunion only to learn some bad news.

“A few months later I'm reading the paper and Frank is in jail for murder. He took a hit out on his business partner,” Cantwell says. “But he sounded like a nice guy on the phone and you just never know who you're talking to, especially former convicts from Alcatraz.”

A former guard steals the show

For many others, the reunions are a chance to share their side of the story and sell books. At this reunion, former Alcatraz guard George DeVincenzi is popular, too. He’s basically a collector’s item; there are only two former guards here.

DeVincenzi is signing copies of his book, Murders on Alcatraz. “Come on in, don’t be bashful,” he says, waving to the tourists.

DeVincenzi was hired as an Alcatraz prison guard in 1950. He says he once witnessed an inmate kill another prisoner with barber shears. Tourists love that story. But DeVincenzi has been talking about it on a loop for the last half a century.

“It was a lover’s quarrel, need I say more?” he says with a laugh. “I've been on BBC, National Geographic about three times. I’ve been on the History Channel, you'll look for me, you'll see me.”

DeVincenzi says talking about Alcatraz is second nature to him now, and that he’s lost the feeling about the prison in the decades since it closed down. After he left his job at the jail, he went to work for United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “Luckily, they took me in, and I went from Hell to Heaven,” he says.

But people won’t stop asking him about Alcatraz.

"I get that question, Did I know Al Capone?" says DeVincenzi. "Al Capone got here in 1934, I didn't get here until 1950, what can I tell you about Al Capone?"

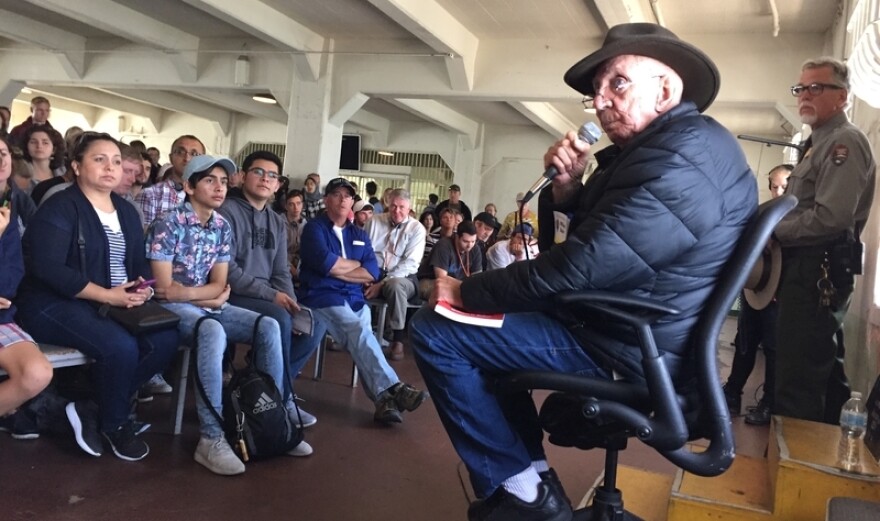

Give it up for ex-con Bill Baker

Tourists pack the old prison dining hall to hear ex-con Bill Baker speak. He’s the only former Alcatraz inmate who shows up in person to this reunion. Ranger John Cantwell pumps up the crowd before the star of the show takes the stage.

“So, without further ado, please give it up for Mr. Bill Baker,” Cantwell says.

After three prison escape attempts Baker was sent to Alcatraz in 1957. There, he says, he learned how to counterfeit payroll checks. This new trade landed him in and out of jail for most of his life. He finally got out seven years ago. By then, he was seventy-eight years old. One person in the audience asks Baker about his path to redemption.

John Cantwell repeats the questions for all to hear: “What do you attribute turning your life around and becoming an upstanding citizen?”

“I just got old,” Baker replies. The audience chuckles with glee.

This is like some dark comedy show. After Baker got out of jail, he wrote a memoir, “Alcatraz 1259,” and went back to the island to rake in the cash and meet with his adoring fans.

"People say, what were you thinking about when you first set foot back on the island? Wasn't that weird?" says Baker. "I was thinking about making money! Selling books."

Cantwell interrupts. He jokingly asks if Baker is telling the audience that crime does indeed pay.

“No, I’m saying hard work pays,” clarifies Baker.

The greatest lesson of all

If tourists are lucky they will catch Baker signing books in the gift shop. He says he sells around 300 books a day. One mom and son find him set up at his table. The son is only ten, but already he has read a lot of stories about Alcatraz. The mom wants Baker to impart some life advice.

“So what’s your greatest lesson?” she asks.

“My greatest lesson is don’t get caught,” Baker jokes.

The mom persists, clarifying that she is looking for something a little more “optimistic.” She asks again, “but what about life lessons?”

Baker just laughs. He’s used to tourists asking him questions. It’s part of his job now. People are interested in his story and he is happy to tell it. He’s says his book has made at least two million dollars in profits. Half of that money goes back to the park service and the island.

“It didn’t bother me coming back at all,” Baker says. “I’m a hundred percent Alcatraz — anything that promotes the island. A lot of it is myth, but I’m not gonna puncture their balloons, I’m not going to say, ‘hey, that’s not right, that ain’t true.’”

Baker got married here on the island. Ranger John officiated his wedding. Alcatraz made him rich, and he’s grateful. He says he’s not scarred by his time behind bars, and that he doesn’t need our sympathy.

“We dealt with it, you know what I mean?” says Baker. “We made home brew, got drunk, walked the yard talking about robbing banks. We had a ball, we jailed it up here. That didn’t mean we loved it, it just meant we could handle it. And that was your average Alcatraz prisoner, not the one you imagine, crying and sniveling all the time.”

At the Alcatraz Alumni Reunions, he’s a celebrity con, and people are here to listen to his version of history.

"All the wardens are dead, I survived this place," says Baker. "It’s my turf now, you understand? So I'm okay."

The final reunion

There aren’t many former Alcatraz inmates left to tell their side of the story. Organizers say that this is the final reunion. The people who lived on the island and served time here are getting old and fading away.

With the ending of the reunions, Alcatraz is making the complete turn from an active prison to a tourist destination. You But you don’t have to go far to find a real working prison. San Quentin is right across the Bay.