Unearthing the Green Revolution, Part III: California's industrial approach to agriculture has long served as a model for government officials in Punjab, India, which dramatically increased crop yields decades ago as part of the high-tech, chemically supplemented Green Revolution. Yet the cost for Punjabi farmers has been a legacy of pesticide reliance, debt, and the hopes for a better life in other countries.

Part I: Drought and debt, from Punjab to California

Part II: A pattern of farmer suicides in Punjab

California large and small

The bustling weekly farmer’s market in Milpitas, California, features dozens of small farmers — such as Khu Yang, who farms six acres in Fresno — selling their fruits and vegetables to passersby.

But it’s the large-scale industrial farmers who grow most of the state’s food.

California was a pioneer of industrial agriculture. In the 1960s, geographer Carl Sauer of the University of

"First we had a lot of cotton. We sprayed it with so many pesticides, and when it was supposed to be ripe for picking, it just dried up." —Punjab farmer Sukhjit Kaur

California, Berkeley, observed that the Green Revolution was an attempt to export the Californian model of agriculture to places like Punjab, in South Asia.

It worked so well that, just as California produces over a third of the vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts consumed in the United States, Punjab farmers are leading grain producers in India.

At the Milpitas farmers market, I ask Yang if there are any Punjabi farmers in Fresno or at the markets he sells at.

"There are," he says, then qualifies his response. "But the funny thing is they’re more the professional ones — the really big ones that do the orchards and the almonds, and the peaches, where they do industrial ag. I’ve seen a couple Punjabis there doing that. Small little farmer’s market, not as much."

Yet back in their ancestral homeland, Punjabi farmers there are nothing like their big-ag California peers.

Punjab's industrial aftermath

At a grain market in Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab, workers sweep wheat into a mound and feed it through a processor. A farmer from a neighboring city, Gurjant Singh, watches silently. He’s just sold 45,000 pounds of grain. But he says his business isn’t going so well.

“I haven’t been able to save anything,” he tells me in Punjabi. “I’m just barely able to cover my expenses.”

Using fertilizers and pesticides has become too expensive for farmers in Punjab — and worse still, they don’t always work.

Two years ago, farmers in the Punjab cotton belt were growing BT Cotton — a pest resistant, genetically modified seed produced by Monsanto, the U.S. based multinational corporation.

In 2015, after whiteflies devastated Punjab’s BT cotton crop, a new pesticide called Oberon was marketed to farmers by another multinational corporation: Bayer.

But farmers say the pesticide failed. Sukhjit Kaur remembers.

“First we had a lot of cotton,” she says. “We sprayed it with so many pesticides, and when it was supposed to be ripe for picking, it just dried up.”

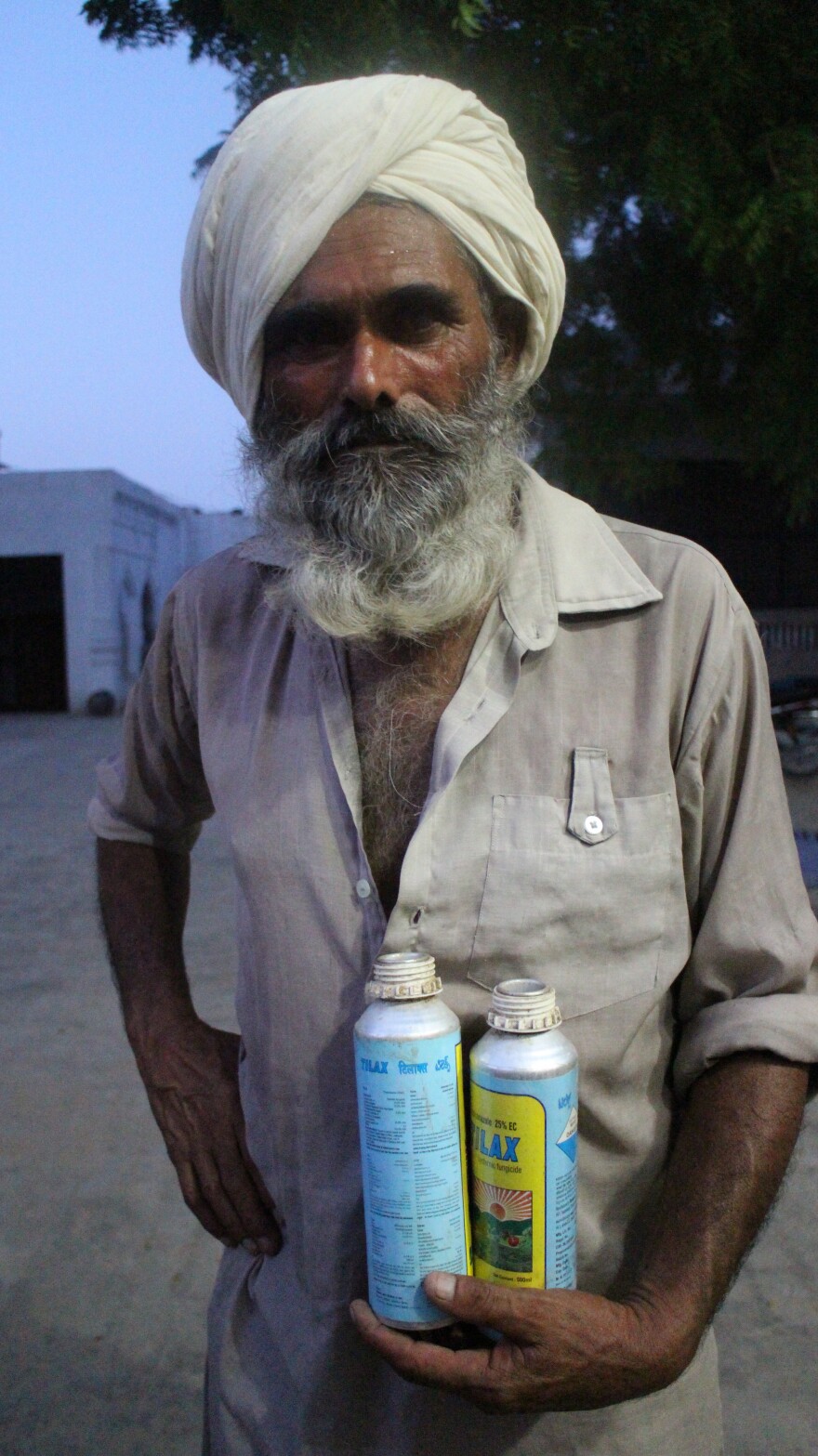

I’m surrounded by a group of elderly farmers in Begelehre, a village in the Bathinda district of Punjab, at the center of Punjab’s cotton belt.

Bathinda has one of the highest cancer rates in the state. There’s a train that departs each evening from Bathinda called the “Cancer Train.” It’s filled everyday with patients seeking cancer treatment in a hospital 200 miles away. I ask the villagers if there’s a cancer problem in their village. A farmer named Bachittar Singh answers.

"At least 10 people in our village have it," he says.

Then everyone beings to speak at once. One man, Bhola Singh, speaks up above the rest.

“The people here are so poor,” he says. “We can’t even afford to get tested. So, we don’t even know if we have cancer or not.”

The villagers say they think the pesticide use is the reason for all the cancer in the region. I ask if they can

show me one of the pesticides that they use.

They bring me a blue and yellow spray can with a picture of the sun shining over a bountiful farm. It’s a fungicide called Tilax manufactured by Axis Crop Science, an Indian pesticide company.

On the back is a warning: “Danger, keep away from people.” It lists the active ingredient as a chemical called propiconazole, which I later find out is listed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as a possible human carcinogen.

“Where can people go? How can they get tested for cancer?” asks Bhola. “Even if they go, no one listens. Only the wealthy get treated, not the poor.”

Regulatory problems

A few days later, I visit a pesticide factory in Derabassi, a city in southern Punjab. The factory is owned by Pioneer Pesticides, an Indian pesticide company. Yashbir Singh Maan, the coordination manager, tells me to put a hospital mask over my nose and mouth before we go inside. He doesn’t put one on though; he says he’s used to it.

The factory floor is large and open. Two giant chemical tanks stand in one corner. Workers in an assembly line bottle and package pesticides.

Some of them aren’t wearing gloves. Or shoes.

I can smell the chemicals through my mask. After about 20 minutes, I’m relieved to be back outside.

Maan flips through the manual that details the provisions of the Insecticide Act, outlining the Indian Government’s regulations on pesticides.

"So there are very strict guidelines to use these products," he says.

"The farmer has no responsibility to tell the government how much of our product he has bought." —Yashbir Singh Maan, a chemical-factory coordinator in Punjab

He says pesticide companies are required to file reports detailing how much product they’ve sold, in order to comply with regulations.

I ask him it it's possible for a company to lie in the records and say they sold less than they actually did, so they aren’t penalized for their extra profit.

He says, “It is possible” — and also notes that farmers are even less constrained. Unlike the United States, farmers are not required to report to the government how much pesticide they use, meaning that they could easily use more than the recommended amount without consequences.

"The farmer has no responsibility to tell the government how much of our product he has bought,” he says. “The farmer only goes to the government when he has a problem with a product.”

That’s what happened when Bayer’s pesticide Oberon didn’t kill whiteflies on cotton plants. Corporations such as Bayer often subcontract with local Indian pesticide companies to have their products made.

“Multinational companies have been in India since the beginning of the pesticide industry,” says Maan. “There were no Indian companies in the field until later. They started up slowly and followed the multinationals.”

He says this trend began with Bayer around the 1980s.

Difficult histories

Bayer began as part of a conglomerate called IG Farben, which during World War II ran its own concentration camps and conducted experiments on Jewish prisoners.

After the war, IG Farben was split into multiple companies, including Bayer, which started making pesticides and herbicides.

Today, Bayer is one of the largest distributors of agricultural chemicals in Punjab, with about 20 distribution centers across the state.

Recently, Bayer announced that it would pay nearly $70 billion to buy Monsanto, another major player in Indian agriculture.

Monsanto and Bayer would not speak with me for this story.

But Monsanto’s sustainability report says that it is working with Indian farmers to increase production sustainably.

It also explains how Monsanto has engaged in philanthropy in India, preventing snake bites and child labor, helping build toilets, and installing solar panels.

But there is no mention of working with the farmers whose BT cotton crops were damaged, or with families of farmers who had committed suicide, a growing problem in Punjab.

Chemical companies hold a lot of power in Punjab, but a small percentage of farmers are not buying it.

"Our Punjab is sick. We need to take responsibility for that." —Parminder Sharma, an organic farmer in Punjab

Back to the land

Parminder Sharma is using a hoe to uproot the weeds on his 11-acre farm — and out of the many farms I’ve visited in Punjab, this is the first where I’ve seen a hoe, and not just a tractor, working the land.

Sharma's farm is organic. It’s in a village called Sunaam in the Sangrur district of Punjab, which was once lauded as one of the Green Revolution's great successes.

Today the district has one of highest farmer-suicide rates in the state.

“At the end of the day we lost more than we gained,” says Sharma. “We may have produced more, but our quality went down. We lost our soil, our water, and our youth who are committing suicide today.”

Before he became an organic farmer, Sharma was a lawyer for 12 years — and his return to his ancestral land was initially difficult. He had to learn how to replenish the soil with natural nutrients.

Sharma opens the lid of a giant black barrel. Inside, is a fermenting mixture of cow manure and yogurt.

He says this was how farmers would fertilize their fields in the old days — and today, it’s what he uses to keep the soil healthy, so that he doesn’t have to rely on the market for seeds, fertilizer, or pesticides.

He’s also in a cooperative, where farmers loan each other equipment instead of buying their own. He uses WhatsApp groups to sell his crops. He grows squash, ladyfinger, bitter gourd, peppers, eggplant, peanuts, turmeric, rice, lentils and wheat.

We go into a mud hut that Sharma built on his farm, where he meditates daily.

I ask him what he wants people to know about Punjab.

“Our Punjab is sick,” he says. “We need to take responsibility for that. What will we say to the next generations, after we’ve destroyed the environment and consumed all the water? How will we face them?”

Sharma works closely with Kheti Virasat Mission, an non-governmental organization that encourages organic farming. In Punjab, according to the organization, less than one percent of Punjab’s total agricultural land is being farmed organically.

In California, it’s actually about the same. Less than one percent of the California’s farmland is organic.

Back in California, I crack open nuts with Sandeep Singh, a Punjabi almond farmer, on his farm in Tracy. He left Punjab in 1997.

"They’re really good," he says, of his prize crop. "Yeah, they taste pretty good these days."

Sandeep is a conventional grower, not an organic one. I ask him why.

"Because when we bought this orchard, it was already three years old," he says. "I didn’t develop it. I didn’t plant the trees, it was already planted. So, it was already too late to go organic. If you want to go organic, I guess you have to start from the beginning."

Singh's answer is a metaphor for the dilemma that the farmers of the world are facing today.

What do you do with the orchard you’ve inherited?

You didn’t plant it, you didn’t develop it, yet you must find a way to make it bloom.

--

This article was made possible in part by the Bringing Home the World International Reporting Fellowship Program for Minority Journalists offered by the International Center for Journalists, with support from the Ford Foundation, the Scripps Howard Foundation, and the Brooks and Joan Fortune Family Foundation.