When the rain arrived this winter, so did a line of tents along Division Street beneath the Central Freeway in San Francisco.

As many as 200 people have been living close together on the sidewalk without permanent housing.

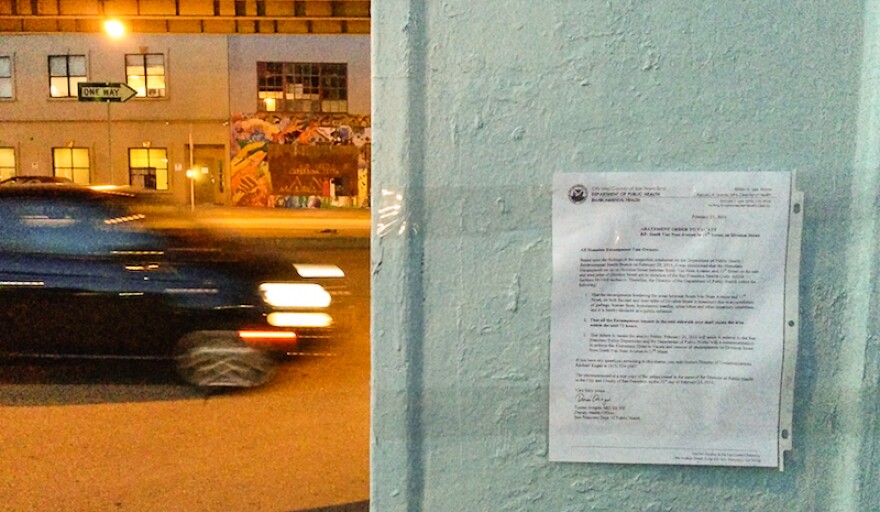

On Tuesday, the city posted notices saying the area is in violation of health codes and that tents had to be gone within 72 hours. But on Thursday morning, Division Street under the freeway was still lined with tents. It seemed tidy, maybe because it was early and the Department of Public Works had just finished their morning sweep.

Perry Foster says he’s been camped here for a couple months.

“They came by and they cleaned that side up and it went well, no problems,” he says. Still, Foster thinks the effort to disband the encampment is pointless. “I think the majority of us will stay. They only gonna do what they always do: toss your stuff and ticket you.”

Since Tuesday, city workers have taken away a dump truck full of waste each day. They’ve filled a flatbed full of people’s belongings, taken it to storage, and bagged and tagged it so people can come get it later. Some commenters on social media have accused the city of trashing people’s possessions without permission, though Foster says that’s not what’s he’s seen.

“DPW has been wonderful,” he says. “It's not DPW, nor is it the police. It's not an adversarial situation as one would think.”

Still, the city wants people off the street by Friday, so the area can be fully steam-cleaned. Foster says he’s tired of packing up and moving. So he’s going to stay put and test his luck.

“It'll be interesting tonight to see if they try to be more assertive,” he says.

Homeless, or ‘camping’?

The notices posted up and down the street state that the encampment is in violation of city health codes “Due to accumulation of garbage, human feces, hypodermic needles, urine odors and other insanitary conditions, and it is hereby declared as a public nuisance.”

Boston Bisbee says she’s been living in a tent for a year. And she says she’s not homeless -- she’s camping. “I'd be homeless if I wasn't in a tent,” she says.

This won’t be the first time she’s had to move.

“We were all over there on San Bruno away from everybody,” she says. “It was just a parking lot. A nice parking lot with all the tents. They came up in there and kicked us out of there.”

Homeless encampments move around the city, but this one seems to be the largest in recent memory. The only other comparable examples are the famous St. Agnos encampment of the 80’s and the tent cities during the time of Occupy San Francisco.

Rainbow Grocery is one of the neighbors that shares the street with the tents.

“We've had people living outside our stores for years,” says Dennis Wagner, Rainbow’s CFO. “The issue is that it's getting to a point where it’s become a public health and safety hazard.”

The grocery and other neighbors have been trying to get the city to address the issue. Flyers, which were available at every check-out lane in the store, asked customers to contact the city about the growing homeless community around them. Wagner says he’s conflicted about the sweeps.

“We can't really fault the city for declaring it a 72-hour emergency to clean the streets because the streets need cleaning,” he says. “We don't agree with the idea of removing people and shoving them to next corner.”

Public health hazard

Tension around this encampment has been building for weeks. So what exactly triggered the public health emergency? Rachel Gordon, from the San Francisco Department of Public Works, explains:

“What our crews have seen -- and we’re out there cleaning the streets every day -- is that there's a large amount of urine, feces, disposed of needles on the ground.”

She says there are a few reasons the encampment’s gotten so big. First, homelessness is up a little bit this year. Second, the rain came hard this winter. And third, there was a huge push by charity organizations to get tents to people on the street. She says that’s what made the clusters really stick and turn into intransient neighborhoods.

“And with the proliferation of tents on the sidewalks,” says Gordon, “we’re seeing that people are being blocked. Pedestrians and people in wheelchairs have to go out into traffic to get by and that's a dangerous situation.”

She says the city’s not trying to clear homeless people from the area permanently -- because that would be impossible. But have there been examples where this kind of cleanup has a lasting impact?

“Well, two blocks of Division Street have lasted for two days now,” she laughs. “They have! This isn't something that's going to be solved easily or quickly or once and for all. This is not gonna end come Friday.”

Where should they go?

Sam Dodge is director of the mayor’s office on homelessness. He also says the sweeps won’t make the encampment go away, but he thinks they will de-escalate the situation. He says the city can’t allow people to live under the conditions at the encampment, and that this is an attempt to offer an alternative.

“They need much more than just a tent,” he says. “At a minimum they need a safe secure place to sleep. They need social work to help navigate our system of bureaucracy and get entitlement benefits and to move on with their lives.”

In the shorter term, he says, “We do have 55 spaces at Pier 80 that are still available. 95 people have come off the Division street area and into Pier 80 over the last week and a half. So it does work.”

Pier 80 is the city’s large, temporary homeless shelter on the border of Potrero Hill and Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhoods. It’s only been open for a week and a half.

Dodge says every day they invite people from Division to come make longer-term reservations at the shelter. They want them to stick around and get set up with a social worker, but they haven’t been able to fill the beds with longer-term reservations. So every evening they take in people just for one night. Every night they’re at capacity, and every morning there is room again.

And here’s where the situation gets more complicated: people like Tamara Hoffner don’t want to leave.

“I'm not going to no Pier 80,” she says. “I'm not going to sleep on no mat when I can sleep on an air mattress in my tent. No. I'm not going to sleep next to no stranger.”

And Boston Bisbee says that shelters downtown have lines and Pier 80 is too far for many people to travel.

“It's the distance thing,” she says. “A lot of these people make their money downtown.”

So where will Bisbee go once she has to leave? She says already has another tent set up in the southeastern part of the city.

“Right on the water, away from everybody. I don't want to give the location!” she says. “Because sooner or later everyone’s going to start migrating over there.”

On Friday, the city says the area must be clear. As of now, officials say they don’t have a plan for people who don’t comply.