If you took walk along the Pillar Point Harbor in Half Moon Bay on a typical winter weekend, it would be buzzing with activity.

“You’d hear a lot of diesels running from everywhere in the harbor, coming and going and staying tied up, and pumping water on their crab. You can almost hear it from the next town over,” says Jake Bunch, one of the harbor’s dozens of crab fishermen, describes.

But right now, it’s quiet.

That’s because scientists found an unsafe level of a toxin in the local crabs this year. It’s there because of a big concentration of algae along the west coast, called algal bloom. The commercial crabbing season is on hold indefinitely.

Jake Bunch got into crabbing three years ago, and spent a lot of money on a permit. He didn’t want to share how much, but a crabbing permit can cost up to $200,000.

“When you jump into this career, it becomes everything for you,” says Bunch. “It's really, really hard to let the boat sit here and go do something else. It's hard on your psyche and it's hard to actually do.”

So right now, most fishermen are spending time fixing up their boats.

“We're hooking up our baiter. It chops up squid, sardines, mackerel,” says Don Pemberton.

Pemberton has been fishing crab since 1976. He’s using this time to do some repairs on his boat, the Stacey Joanne, but he’s worried.

“It’s pretty scary. I’ve never been without income this time of the year. It's been five months since we’ve done anything.”

Finding other ways to pass the time

Most of the other fishermen here feel the same way. Some have left their boats behind to look for temporary work, like construction or odd jobs. Others bought permits to fish other species, like rock cod. Some fishermen, like Jimmy Anderson, are using this time to focus on side projects to help out the fishery.

“We have a fleet of boats out that are picking up lost and derelict pots and bringing those in,” Anderson says.

Anderson’s been fishing crab since out here he was in high school and has watched the fishery grow from 100 boats, to more than 400.

He says he’s hoping the Department of Public Health, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife will reopen the fishery before the Christmas season, when crabbers make a lot of their income. Four Congress members have actually called on Governor Brown to create a relief fund for fishermen, if the season gets canceled entirely. But even if it doesn’t, he’s worried about what could happen next year.

“I’ve heard scientists on both ends of it, [saying] that this is the new normal and this is gonna be forever. And I’ve heard scientists that say, ‘You had it in the past for a period of time and it went away and the crabs were fine and everybody just got on with life,’” Anderson says. “So I don’t know. I don’t try to guess the future in those respects, but it’s definitely a concern right now.”

Toxic blooms could be the new normal

Clarissa Anderson (no relation to Jimmy) is a biological oceanographer with U.C. Santa Cruz. She says it’s normal for toxic algae to turn up in the ocean like this. But usually it’s just for a couple of weeks.

“The idea that we would have a bloom that goes on for five months – I don't think anybody anticipated that,” she says.

The bloom stretches from Santa Barbara to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska. And it’s made up of algae, or phytoplankton, that produce a very powerful neurotoxin called domoic acid. Scientists still aren’t sure why they produce this toxin, but they do know that warmer than usual ocean temperatures are contributing to the problem.

“So that has changed a lot of things in ecosystem and the environment is responding in ways we couldn’t even predict,” says Clarissa Anderson.

Crabs don’t eat this algae – animals like clams and mussels do. And then, the crabs eat them. The toxin doesn’t actually hurt the crabs, but it’s bad for whoever eats the crab. If birds eat crabs, they get disoriented, fly around in circles. If humans eat crabs with domoic acid, we could experience seizures, memory loss, or die. Eventually crabs can naturally rid themselves of domoic acid, but it takes a while.

Anderson says we’re already starting to see the crabs have lower levels of domoic acid in places like Half Moon Bay and San Francisco. But even if it clears up now, it could come back next year.

“It may be that this is an anomalous thing that we may not see for a while but a lot of people particularly in the climate sciences are predicting that this is a harbinger of things to come,” says Anderson. “If this the case, then this kind of strange unpredicted bloom that we saw in relation to the warm water could be become more normal.”

The testing process

The Department of Public Health has been testing crabs all along the coast, measuring their levels of domoic acid. Fisherman Ben Platt volunteered to go out and collect some for the most recent test.

On his boat, he has three blue buckets. They each hold two giant Dungeness crabs. Each bucket represents a different depth.

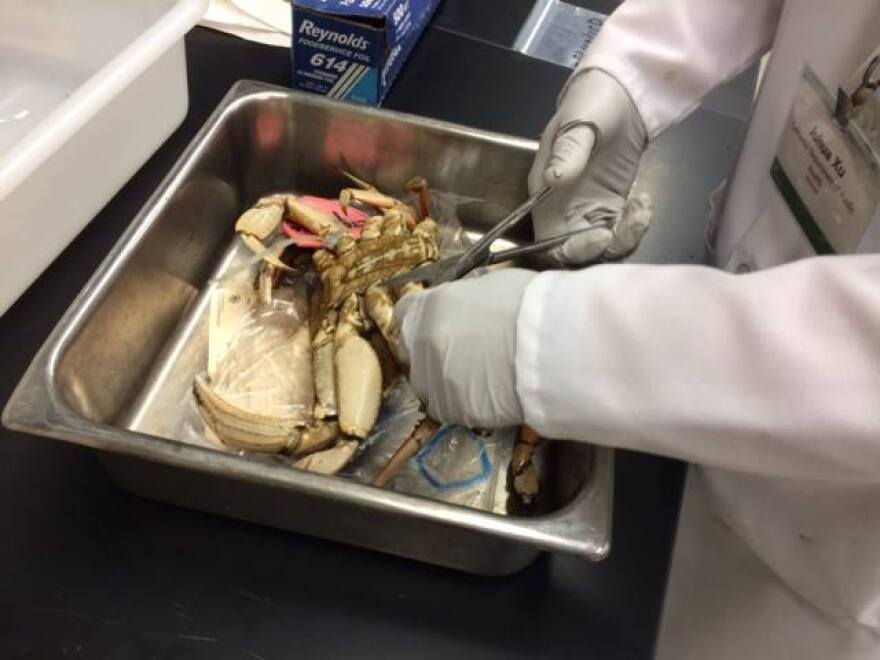

The Department of Public Health will pick the crab up from Platt and other fisherman along the coast, bring it to a lab across the bay in Richmond, and stick it into a blender. Then, they’ll measure the toxicity from the blended crab. From those results, they’ll determine whether it’s okay to open all or parts of the commercial or recreational fishery.

“There’s a difference between this industry and a lot of other ones that have problems...with most food items people don’t find out about it until somebody’s already gotten sick,” Platt says.

Crabs don’t respect boundaries

There still isn’t any word on when the crab season will open. Platt says he hopes they won’t lose the entire season. And he wants the recreational fishery and the commercial fishery to open at the same time. He doesn’t want one crab to tarnish the reputation of the $60-million industry.

“It would be better to sacrifice the holiday market for one year and be able to have have consumer confidence for years to come. If the state were to do the wrong thing, it could ruin it for years to come,” Platt says.

When the crab season opens again, Platt hopes people do what they’ve done for years during the holiday season: buy lots and lots of fresh, local crab.