Seventeen-year-old Elisa Morris-Jackson is sitting on the couch in sweatpants and a hoodie. It’s seven p.m. and she’s watching the TV show “Dancing With The Stars.” Seven p.m. each evening is also the time when about 130 other juvenile offenders in Alameda County, California are required to plug in and sit down for their mandatory two-hour battery charge.

“I’m going to be so excited to get this thing off of me,” she said.

Jackson has a GPS monitor fastened around her ankle with a rubber strap. It’s part of her probation. The GPS unit is black and plastic — about the size and shape of a computer mouse — with three LED lights and a big button. Its purpose: to track her every movement.

Where does that information end up? At the Juvenile Justice Center in San Leandro, California. A probation officer named Chris showed me how GPS monitors work.

“We use Google Maps, and it shows real time. So this kid we released today, and this shows us that he was here at the Juvenile Justice Center,” he said, pointing at the computer screen.

We are looking at the digital breadcrumbs of one teenager’s movements since he was released from juvenile hall, just an hour or two ago, and fitted with a GPS monitor.

The map shows the teen’s path out of the building to the parking lot. Then down the hill to the freeway.

“It’s very high tech,” said Chris. The officers can even tell if a teenager is in the front yard or backyard of their home.

The probation officer drags a green circle over the kid’s home. On the scr een, it’s about two inches, but in real life it represents a radius of 150 feet. That’s the zone the kid is restricted to. Outside of that, it would be a GPS violation and a judge could send him back to juvenile hall.

Teens on GPS monitoring have to call their probation officer before they leave for school in the morning. And anything outside of school and home — like a job — requires special permission at least 48 hours in advance. So it’s basically house arrest.

Alameda County District Attorney Nancy O’Malley said GPS monitoring saves money because it costs a lot less than incarceration. In fact, locking a kid up in juvenile hall costs about $429 per day. GPS costs only $85. O’Malley credits the surveillance technology for helping to keep young people at home with their families and out of incarceration.

“When they were originally building a juvenile justice center, the original idea was that it was going to be more than 500 beds,” said O’Malley. “And I think that on any given day now, there are less than 200.”

While incarceration is down, use of electronic monitoring like GPS has increased, more than tripling in the last 10 years. And the devices cost families up to $15 a day.

Dominique Pinkney is a juvenile public defender in Alameda County. He’s glad to have more kids out of jail, but he has big problems with GPS. “It’s absolutely overused,” he said. Pinkney argues that judges assign it almost reflexively, even to teens who never would have been sent to juvenile hall. Not only that, Pinkney said it’s too restrictive and teens get in trouble for silly reasons, like not keeping their device properly charged or hanging out with friends.

The consequence of these violations? Lengthening teens’ probation or even sending them back to juvenile hall.

“When you extend the consequence beyond some rational period, it becomes abusive. It makes kids angry. It actually has the opposite effect,” said Pinkney. “So you engage in a battle instead of sending a corrective signal.”

Nearly half of the young people who are electronically monitored end up violating the terms, according to a report cited by the American Bar Association. A quarter cut the device off entirely.

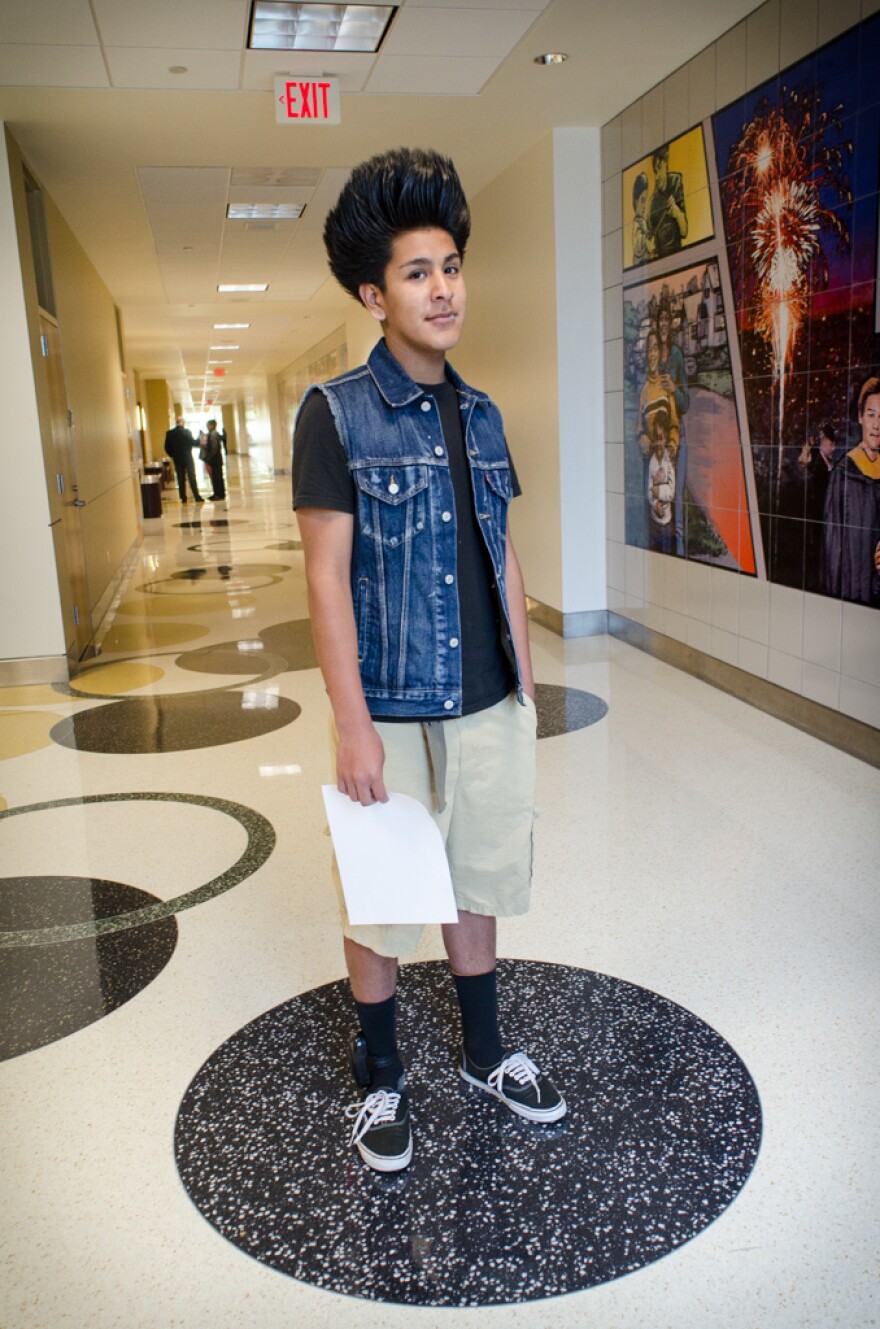

Sixteen-year-old Manny Velazquez is waiting outside of a courtroom. He’s wearing a denim vest, black t-shirt, and khaki shorts. Besides his towering spiked hair, the most noticeable thing about him is the GPS monitor strapped around his ankle, which he’s wearing over his high black socks.

“I am ashamed of it. But that’s not stopping me from…being myself, of the way I dress,” he said.

Velazquez says he was sent to juvenile hall after missing too much school. Yes, you can be sent to jail for truancy in some places. He says he’s been on GPS for more than three months since his release. For Velazquez, the worst part is the isolation.

“It’s just the same routine over and over,” he said. “Go to school. Come home. Sometimes I do get frustrated because I feel like I’m trapped in my own house. Just last night, I felt like the walls were closing in on me.”

One courtroom away, 15-year-old Cameron Lopes had just met with a judge. He was caught carrying a pocketknife in school and spent five days in juvenile hall. Then he was strapped with a GPS unit for 30 days, after missing a court date. Today he and his dad, Jamie, were hoping they could get the device taken off.

Jamie walked out of the courtroom as the heavy wooden doors thumped shut behind him. “He didn’t get his GPS off today,” he said.

Cameron was pissed. “I’ve been trying real hard and they just throw all the bad stuff in there and never the good stuff.”

Jamie added, “It’s just little stuff that happened at school. If he got mad at school, they brought it up. If he yelled at somebody, they brought it up. They didn’t bring up that he was on the honor roll. It’s just a lot of negative stuff. So, another 30 days.”

But, just four days before that 30 days was up, Lopes got into an argument with his dad and cut off his GPS monitor and was sent back to juvenile hall for nearly a month.

Judges, DAs and public defenders are in rare agreement, that GPS tracking is a good alternative to incarcerating teenagers.

And it does save money.

But for the young people being monitored, the technology may be solving one problem and creating others, like extending their time in the criminal justice system.

This story was part of Double Charged, a special investigation into the juvenile justice system produced by Youth Radio. For the other stories in the series, click here.