For decades, the story of the Compton's Cafeteria riot was lost to history. Few people knew about the courageous drag queen who fought back against police with a cup of hot coffee, or the transgender women who took to the streets that night. But now a theater piece is bringing that act of resistance back to life.

More widely known are the Stonewall Riots in New York City in 1969, often cited as the spark that lit the nation’s contemporary gay liberation movement.

But before Stonewall, there were lesser-known queer rebellions around the country. The Compton’s Cafeteria Riot is one such uprising.

Reliving the riot

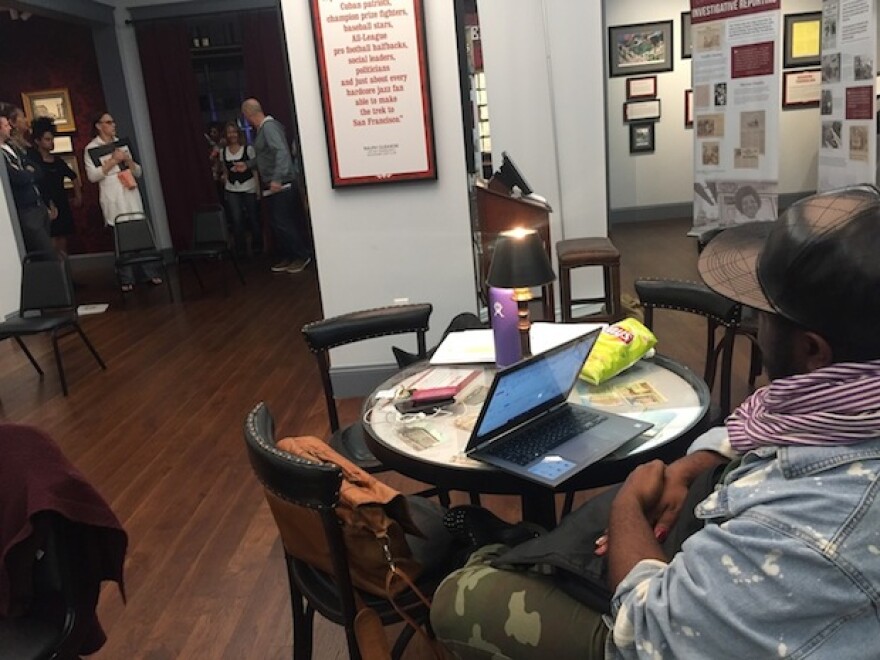

During a rehearsal at the Tenderloin Museum in San Francisco, actors are reenacting the riot that erupted at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria more than half a century ago.

In this scene, it’s a hot, August night in 1966. Drag queens, transgender women, and street hustlers are dancing and singing — when a cop walks in.

"It seemed like a hundred screaming queens showed up with all their collective rage, uncorked. But we busted everything in sight, we burned a cop car. Some queen threw an M-80 in the gas tank, it just blew up."

“What kind of clown act is going on here? Of course you can’t act like human beings, because you’re not,” the police officer, played by actor Joseph Paul, asks venomously.

An officer tries to arrest a character named Rusty for female impersonation.

"That’s it. Turn around, you’re under arrest, come here," the cop says.

So, Rusty, played by Shane Zaldivar, throws a cup of coffee in the cop’s face. The cop yelps in pain, then shouts, “You freak!”

In the historical uprising, forks and knives flew in the air and tables were turned upside down. The fight spilled out into the street.

“It seemed like a hundred screaming queens showed up with all their collective rage, uncorked,” Kelly J. Kelly, playing Vicki, says. “But we busted everything in sight, we burned a cop car. Some queen threw an M-80 in the gas tank, it just blew up.”

Donna Personna finds her Disneyland

Drag queen Donna Personna is one of three people who collaborated on the script, along with Colette LeGrande and Mark Nassar. Raised by a Baptist minister, she was taught from an early age that being a gay or transgender person was wrong.

“It was against the law to impersonate a woman," Personna remembers. “I would open a medical book, and I saw that it was an illness or an anomaly and something that needed to be removed from your psyche somehow.”

In the mid-'60s, when Personna was 18-years-old, she would take the Greyhound bus from San Jose to the corner of Turk and Taylor in the Tenderloin to Gene Compton’s Cafeteria.

The diner isn’t much now, just a big building with boarded up doors. But back then, the diner was like a 24-hour portal to another world. It was jam-packed with night owls, sipping cups of coffee that cost less than a dime. Transgender people weren’t welcome in the gay bars nearby, so they went to Compton’s.

“So I come here, and I’m normal!” Personna says. “It was better than Disneyland, better than Paris. We had to not tell the world at large about this because then they would destroy it for us.”

Rolling with a tough crowd

Many of the trans women Personna befriended lived in a crowded Tenderloin hotel room, and did what they could to survive.

“I learned that they were sex workers. They took and sold drugs. They were shoplifters,” she says. “And they were all wonderful people.”

Compton’s was like a late night office, where the women could come down from highs, gossip, and warn each other about police or angry johns. They just wanted to be themselves, but the world wanted them to be a gender they didn’t identify with. It was nearly impossible for transgender people to find work.

“They would love to have been a schoolteacher if they could do it as a woman,” Personna says. “You know give me all my rights and you know I'll pick something out. But you know they had to sleep somewhere at night. And the only thing there for them was streetwalking.”

Burying history

Donna Personna was hanging out with a rough crowd. One night, she was riding in a car with her drug-dealer boyfriend, and someone shot at them. She decided to quit the scene, and left the neighborhood. Over the years, she discovered LSD, became a hippie, and moved on.

She had no way of knowing that soon afterwards, the Compton’s Cafeteria queens rebelled. Newspapers ignored it.

“Nobody gave a hoot. I’m going to be nice and not talk dirty. But basically nobody cared about these people,” Personna says. “Not their families, the public, and certainly not City Hall. The whole story was buried, as though it never happened.”

Digging through the archives

That is, until this history was unearthed by Susan Stryker, a gender and women’s studies professor. Back in the ‘90s, while in the process of transitioning from male to female, she yearned to find a real-life story about transgender people that described more than hormone therapy and surgery.

“Trans people have existed. It's like we have to have come together and been involved in struggle against oppressive forms of power,” Stryker says. “It's like, that story has got to be there.”

After paging through files of old newspapers and pamphlets at the GLBT Historical Society, she found a mention of a riot in a program from the 1972 Pride Parade — ancient history when it comes to queer rights.

“So when I came across this story, I thought, ‘This is it,’” Stryker says. “It’s not a story of medicine and psychiatry, but a story of people finding the ability to live in the world the way that they want to live.”

Social justice and 'Screaming Queens'

Stryker spent the next few years piecing together that story. Then, in 2005, she released a documentary, called Screaming Queens, to set the record straight about the Compton’s Cafeteria uprising.

“What happened at Gene Compton's Cafeteria wasn't a catfight between screaming queens, it was a riot and it kicked off a new campaign for human rights,” Stryker explains in the film.

It was the summer before the Summer of Love. Stryker says that as the Vietnam War escalated, more soldiers and sailors went to the Tenderloin to buy prostitutes.

So in an effort to clean up the city, police raids intensified.

The Vanguard, a radical, gay advocacy group, pushed back. They were inspired by the anti-war organizers a few blocks away at Glide Memorial Church, student protesters across the Bay in Berkeley, and civil rights marchers on the other side of the country.

But what put things in motion was that dramatic moment right out of a movie: a drag queen splashing a cup of coffee in a cop’s face.

After the riot, things quietly began to improve for transgender people in San Francisco. They gave talks at the police academy. Charities such as the Salvation Army, and public-health staffers, all worked more closely with the trans community.

“It was a pretty remarkable network of things that came out of trans people on the streets pushing back against the police,” Stryker says.

Honoring those fierce, forgotten trans women

Donna Personna had left town before all this. She was able to escape the Tenderloin because she had a loving family in San Jose to go back to.

She says she co-wrote the Compton’s Cafeteria play in order to honor the women who couldn’t leave.

“They were born, they lived and then they died not getting endorsed by the universe. They didn't get that. But I want to give them that,” Personna says.

In the Compton’s Cafeteria play, a character named Vicki reflects on the riot from the present day.

“Back then, it was different, so different. And yet today, the same battles still rages on. Back then, we were battling for a few blocks of dignity, today the battle is for our country,” Vicki says in the play.

The Compton’s District

After the upheaval, activists made progress, until eventually, finally, being gay or transgender was no longer a crime.

“But still, how many transgender people were murdered this year, and last year, and for what?” Vicki says. "For being themselves, which is still, unfortunately, a courageous act."

San Francisco city officials plan to establish the country’s first transgender cultural district in the Tenderloin. Even now, if you wander by Turk and Taylor, you’ll see a sign that says Gene Compton’s Cafeteria Way.

But that still leaves out the part about the riot.

The Compton's Cafeteria Riot theater production is running until March 17th at the New Village Cafe.