Would you choose to pay a tax that you didn’t legally owe? A group of indigenous women in the East Bay have gotten together to ask for just that. They’ve levied a tax on residents for the land they are living on.

Taxes can be pretty serious business: if you don’t pay the IRS, you owe extra taxes and eventually the government can take away your passport, throw you in jail, and even seize your land.

That last one is especially familiar to Corrina Gould, spokesperson for the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, whose ancestors lived for millennia on the shores of what is now known as San Leandro Creek.

When she introduces herself, it’s in Chochenyo.

“The Chochenyo language is the first language of the East Bay people,” she explains. “There were actually eight different tribes of Ohlone people with eight different languages and eight different creation stories. So we're actually different nations.”

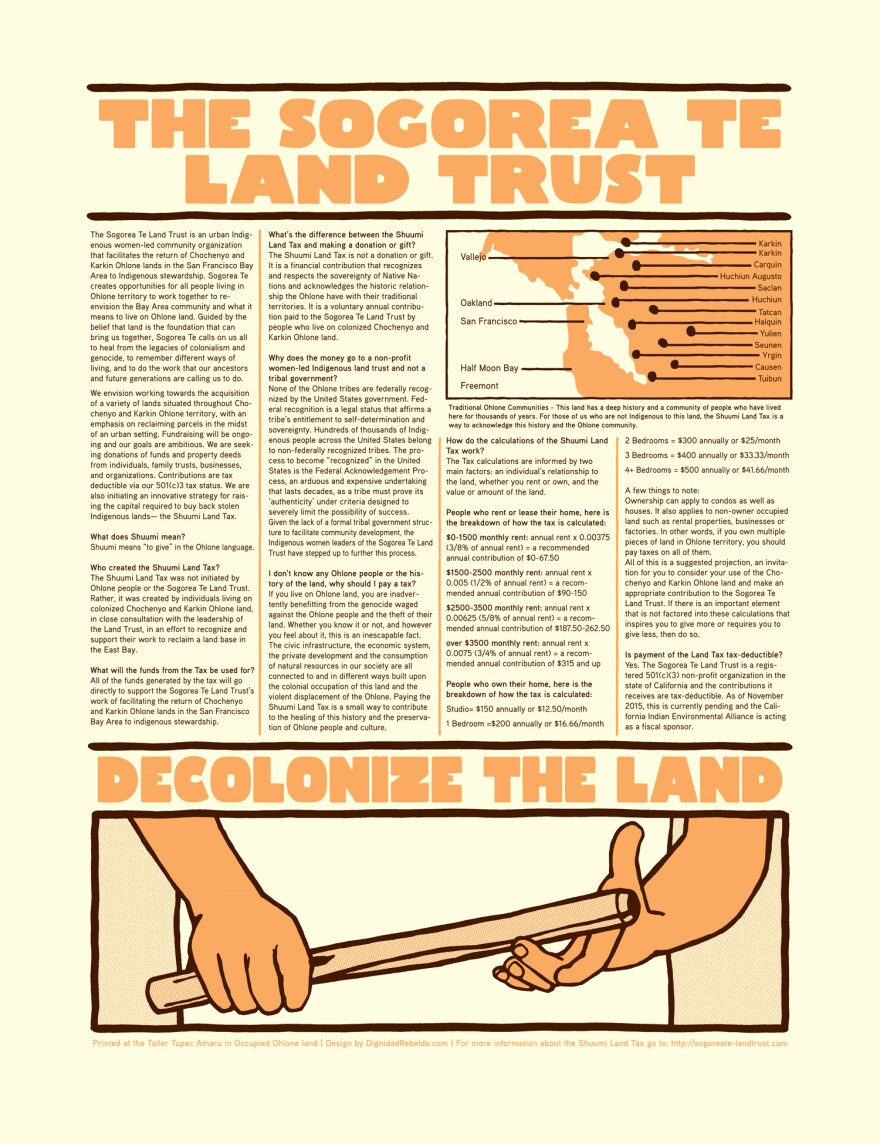

And she is one of the co-heads of the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, whose mission is to bring Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone lands back under the stewardship of Native Americans.

Their novel means of doing so is what they’re calling the Shuumi Land Tax.

Voluntary tax

“Shuumi,” she translates, “means ‘a gift.’”

They’re asking all non-indigenous residents of the East Bay to pay a certain amount, depending on their home size or rent. And this isn’t a tax that goes through the IRS — it’s voluntary.

According to the federal government, it’s the same as donating money to any nonprofit. You just go the land trust’s website and pay through PayPal.

But they don’t call it a donation. Saying it’s a tax asserts their sovereignty, and implies they have the authority to tax. Gould and her co-founder were originally wary of even calling it a “tax” because of negative connotation with that word, and because they don't believe that land should even be able to be purchased.

But they found the framing was effective.

“I think that people understand what that word ‘tax’ means,” explains Gould, “and I think they are willing to be able to participate in that kind of way.”

Here’s how it works: The Land Trust suggests that you pay the tax annually. If you rent, then it’s a small portion of that annual rent — less than one percent.

And if you own a home, it’s calculated by bedroom. It works out to between $67.50 to $500 a year.

But those numbers are recommendations: People can pay what they want, when they want.

And they do. Last year the program brought in $80,000 from 800 specific contributions.

Since the Ohlone aren’t a recognized Native American tribe by the federal government, there are many rights they don’t have.

If they did have recognition, they’d be given land, get medical insurance, and be able to collect certain taxes on their land.

So the land tax is one way to obtain the resources they are denied by a government which doesn’t acknowledge their existence.

Historic obligations

Beyond bringing in money, the tax is also a way to promote the idea that non-indigenous people have an obligation.

Gould is firm about it. “It's your responsibility as settlers that come onto our land,” she says, “to actually give something back, and this is an easy way of doing that, a way for us to heal the horrific past that's not that long ago.”

The land tax launched in 2015. It was inspired by a similar program called the Honor Tax that benefits the Wiyot tribe in Northern California, and has been going for about a decade.

In 2017 a similar program was adopted in Seattle for the Duwamish tribe. They call it Real Rent.

This is an idea that is spreading.

Unlike your income tax to the federal government, there aren’t traditional repercussions for not paying. The Sogorea Te’ Land Trust can’t put a lien on your property.

So why would someone pay? Are there any repercussions for not paying?

“That is based on people's own ethics and morals,” says East Bay resident Haleh Zandi, who pays.

For Zandi, t’s a tangible way of acknowledging the horrific treatment of Native Americans in California.

“I want to see Ohlone people gain access back to their land and save their ceremonial sites,” she says, “save their sacred sites, and become recognized and respected as people who have survived colonization and genocide.”

And the tax really is helping. Corrina Gould first starting thinking about a trust to protect native lands back in 2011. Four years later they had enough resources to really establish the land trust.

By the end of 2017, they were gifted their first piece of land, by an organization that Haleh Zandi helped co-found.

A piece of land

On a quiet part of 105th Avenue in Oakland’s Sobrante Park neighborhood, Gould walks by a line of small fruit trees.

“So where we're walking to, the back part of the land, is actually Sogorea Te’ Land Trust area,” she explains.

An organization called Planting Justice owns two acres of land here. They have a nursery staffed mostly by people who are formerly incarcerated.

Right now, they’re in the process of creating something called a “cultural easement.”

That will permanently protect one-quarter as an Ohlone cultural site, no matter who may own it in the future.

And once Planting Justice pays off their loan on the property, they’ll give the title to the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, and then they’ll lease back the land for their nursery.

At that point both organizations will work together on the land, but with the indigenous-run land trust having the control.

And even though these two acres are right next to the I-880 freeway, it feels open and calm here.

Gould says this is specifically the area where her ancestors lived: “It totally is someplace you can imagine people have been for thousands of years.”

They’re about to build an arbor with a fire pit in the center, where they’ll have traditional dances. They’re also planting native plants that are used for medicine and basket weaving. The hope is to establish a checkerboard of land around the East Bay and eventually build a roundhouse.

“A roundhouse,” Gould explains, “is our spiritual center. It's a place we haven't had in our own territory for 200 years. It's a way for us to actually do what what our obligations are: to sing and dance our songs to heal the land.”

With all this talk of taxes, I wanted to know how Gould felt about having to sit down every April to pay her own income tax.

She laughs.

“I don't know ... sometimes when you're a native person you just don't want to think about things like that,” she says. “One of these days it would be great to sit down with some folks that are senators, and talk to them about how is it possible to not pay these taxes on land that was stolen from us.”

For now, Gould and her colleagues have to go over the head of the U.S. government.

The Shuumi land tax is a way to bring resources to native people who were here for thousands of years before the IRS even existed.

Learn more about the Shuumi Land Tax on their website.