As the tallest building in San Francisco, Salesforce Tower is the new center of the city skyline. And starting today, the top of the tower will also become a work of public art, created by San Francisco artist Jim Campbell.

During the day, cameras installed around San Francisco will record movements like waves crashing on Ocean Beach, trees blowing in Golden Gate Park, and pedestrians crossing Market Street. At night, the images will be projected onto the top of Salesforce Tower like a visual diary of the day. The permanent installation is called “Day for Night.” Campbell says he named it after the filmmaking technique where a scene is lit during the day to make it look like it is night.

Salesforce Tower is 1,070 feet tall and has 61 floors of office space wrapped in glass. But the top six floors, called the crown, are wrapped with over a hundred and thirty perforated aluminum panels. The components in “Day For Night” are installed directly into these panels, with about eighty pixels bolted to each piece of aluminum. In total, over 11,000 pixels will create a hundred-foot tall circular LED screen.

Campbell says that, during a trip to Hong Kong, he watched the skyline blaze and blink like an elaborate LED light show, and thought that it wasn’t a very pleasant aesthetic.

“So a part of me was: why am I creating this thing that I don’t necessarily believe in from an urban planning perspective?” he says. “On the other hand, I took that as a challenge, and said: Okay, what can I do in this skyline that will work, that will fit in without completely changing the skyline? I really don’t want to do something that I would call spectacular. I don’t want it to be flashy.”

To start, Campbell changed the way the pixels are mounted by turning them inward. On the buildings in Hong Kong, the pixels face away from the building, shining bright light into the sky.

On Salesforce Tower, they extend outward from the panels — like camping headlamps on selfie sticks — and shine light back at the aluminum panels, creating a soft glow against the gray aluminum.

The moving images will be projected in low-resolution, so you might not be able to determine what the image is at first glance. As far as Campbell knows, it’s the first time pixels have been installed this way on a building and the first time public art will be injected into a city skyline like this. But even he isn’t completely certain about it.

“I see this more and more as a big experiment,” he says. “What could go wrong is that people don't want to see an image in the sky. We don't know. Do you know if you want to or not? I don't.”

‘Unachievable high plateau’

Today, Campbell’s artwork hangs in major museums worldwide. His public art is installed in places like Grace Cathedral, the San Diego Airport, Dallas Cowboys Stadium, and Battery Park.

As a kid, he didn’t think he would become an artist. He grew up in a lower-middle-class suburb of Chicago. “When I was growing up I never met an artist, so I never knew it was an option,” he says.

He graduated from MIT in 1978 with degrees in mathematics and electrical engineering. In Silicon Valley, he worked on algorithms to convert standard definition TV images into high-definition TV images. In his spare time, he created digital art in a studio converted from his Potrero Hill home's garage.

“I was doing art for at least ten years before I called myself an artist,” he says. “I always had artists on this unachievable high plateau.”

He no longer calls himself an engineer, but still designs the electronic components used in his art, including the pixels on Salesforce Tower.

Campbell's work explores the boundaries of perception. With “Day for Night,” he wants to challenge what we expect to see in a skyline.

“It's an interesting public-art challenge,” he explains, “in that a million people are going to see this at night, whether they want to or not … So it's a challenge, to have it fit in, have it be subtle, have it be engaging, changing, and dynamic.”

San Francisco’s anti-high rise history

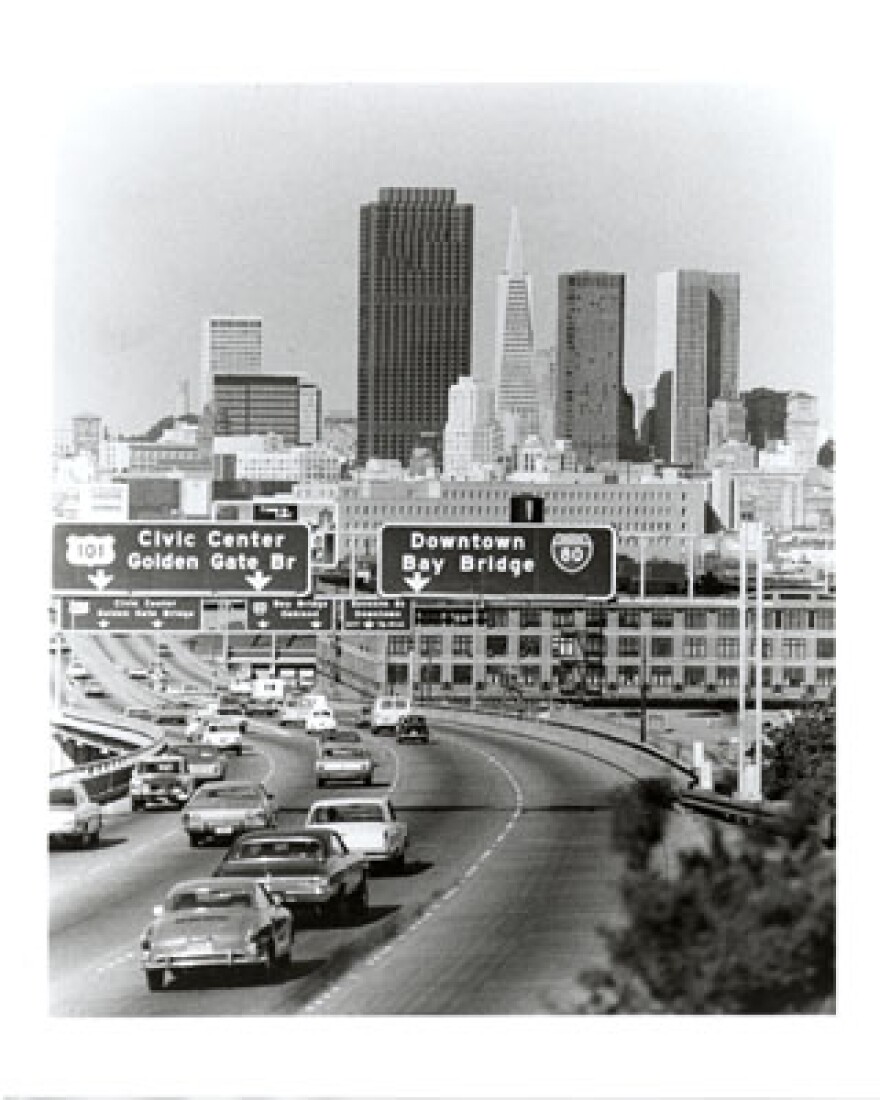

San Francisco has hardly been a city to embrace changes to its skyline. In the 1960s, where residents saw natural hills downtown, developers saw opportunity. Big, boxy buildings shot-up without oversight.

Joshua Switzky, a lead planner with the San Francisco Planning Department, says a backlash against tall office buildings took root among critics and residents.

“That created theplanning framework to more consciously shape the city's skyline based on public values and intention, and not on private initiative,” Switzky says.

That framework was called the Downtown Plan. By the time Mayor Diane Feinstein signed it in 1985, it was described as one of the most publicized and scrutinized pieces of planning legislation in the country’s history.

“That plan required that tall buildings taper as they got taller and emphasized more delicate and interesting tops of buildings,” he says.

To avoid refrigerator-like buildings, the plan required tops to be complex, decorative, sculptured, intricate, expressive. Architects bristled. Allan Temko, San Francisco Chronicle’s architecture critic at the time, quipped that San Francisco wouldn’t need architects, but milliners.

“Putting silly hats on tops of buildings,” Switzky explains, “and there certainly are buildings that that’s probably a fair representation.”

An “anti-high rise” movement was born. Back then, Tim Redmond was a reporter for the San Francisco Bay Guardian. Today he’s the editor of 48hills.org, the Guardian’s online successor.

Redmond says the movement wasn’t against high rises or how they looked. “The Bay Guardian was very much proudly of what was then called the ‘Anti-High Rise Movement,’ but it was more than that. It was an urban-environmental movement that wanted reasonable, rational planning in the city.”

In the 1970s the Guardian published the book, “The Ultimate Highrise: San Francisco's Mad Rush Toward the Sky.” It’s thesis: San Francisco high rise development was not financially viable.

The book proved that growth was not paying for growth, Redmond says. “When you do commercial office development, you attract workers to those buildings. How are they going to get there? Where are going to live? What's going to happen if they need emergency services? And who’s going to pay for all of that?” Not the developers, he adds.

We sat in Dolores Park overlooking Mission residential neighborhoods in the foreground with the downtown skyline rising beyond.

“Thirty years ago there were low income working class people living here,” he said. “And most of them are gone and that's because of what I see right over their heads. That’s because of what I see downtown. So I'm glad that we require a fee for public art. And that’s a wonderful thing. I'm all in favor, I'm glad they're doing it. What is that going to do for the family who is being evicted in the Mission because the landlord wants to rent it out to someone who works in Salesforce Tower?”

The planning department still dictates the aesthetics of San Francisco urban design — and a policy in the Downtown Plan requires developers spend one percent of construction costs on public art. Typically, this produces street-level art like sculptures, paintings, and digital works.

But the city has no oversight on the actual art. So here, it’s the developers, Boston Properties, and Jim Campbell who get final say over the new “hat” that will top Salesforce Tower — and change the city skyline.

Whether people like seeing images or not, the San Francisco skyline is about to change, as fast as the city it reflects.

This story originally aired in November of 2017 and has since been updated.