Climate change is an issue that can be hard for some to prioritize. It’s abstract. We can read the charts and the statistics—but is there a way to feel it? The Bay Area’s Climate Music Project at UC Berkeley wants to make the experience visceral.

It’s a collaboration between data science and music that tells the story of how the climate has changed in the last 200 years, what we can expect in the future, and how we can all help address what’s arguably the greatest challenge facing humanity.

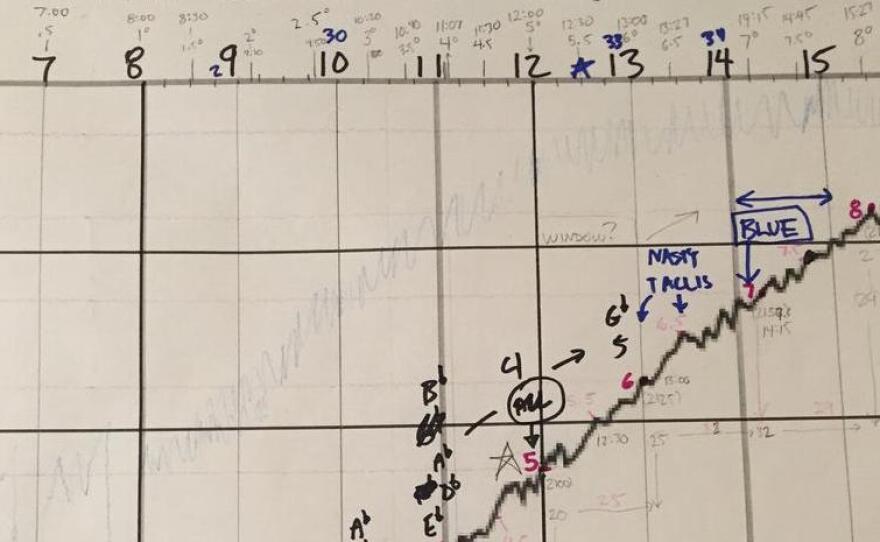

Meet Erik Ian Walker. He’s a composer, a self-described alchemist with sound. His music studio looks pretty much how you’d expect – one side’s dominated by a big mixing console with all kinds of knobs and buttons and lights. Big speakers sit in the corner. A few feet away, a piano is strewn with sheet music. And then,there are all the scientific graphs pinned up on his wall.

“So we have all these curves, right?” he says, showing me the intricately mapped data on his wall. “There's sea ice, the pH of the ocean, the incoming and outgoing long wave radiation, which is actually kind of the big thing. CO2 increase. And air temperature.”

The graphs show climate change --- how it’s projected to affect our world, and how it has already. But for most of us, it’s all numbers and lines, plotting incremental changes over time. Walker’s job is to translate this data into music – to create a composition that will let listeners feel how climate has, and might change over 500 years – from 1800 to 2300. All in the course of 30 minutes.

“The scientific data is very real,” says Walker. “I’m following it rather religiously, if I can use that term, to make it happen, but there’s still the human element in it.”

What he means is that he’s using his skills as a composer to create something people will actually want to listen to --and be able to tolerate.

“It's all about where people will follow you and how can you invite them to keep going down that pathway, even when the notes start to become really really different for them,” he explains.

Walker plays me some samples. We start with the sound of the environment before the Industrial Revolution. It’s beautiful music, soothing.

“This is when things are just sort of stable and not changing,” Walker tells me. “But we do have the violin weaving in and out and there's a little bit of an orchestral sound.”

The violin represents humanity. In the performance, musicians will play live on stage against the backdrop of Walker’s composition -- the human element interacting with the ongoing changes in the background of ambient sound he’s making in the studio.

Walker has assigned musical properties to all those climate change graphs on his wall – so, increases in air temperature change the pitch; higher levels of carbon dioxide speed up the tempo; solar radiation distorts notes.

“Precipitation,” he says “Is good old white noise.”

As the piece progresses, he starts to let the course of climate change affect the melody. You can really start hearing changes around the year 1950 -- that’s when CO2 levels first start to noticeably rise, and the temperature begins creeping up.

Just fifty years later, by the year 2000, the temperature has gone up one full degree Celsius – that’s where we still are, right now, in 2015. One degree might not seem like a lot…until you hear it.

By the year 2025, projections show the temperature rising another full degree. 20 years, instead of 200. Climate change is starting to happen faster.

“That two degrees is where we'd ideally like to hold things,” says Walker. “So we're going to hear the bass guitar and the piano and the drums playing along, just seemingly playing a little song, and there's some leaves blowing and a little bit of rain.”

Walker says this is where climate scientists are pushing for us to stay, if at all possible. To do that, we’d have to cap all carbon emissions by the year 2100. Even if we do that, Walker says temperatures will still continue to rise, though more gradually. But if we don’t...

“It starts to really go up,” he says. “So three degrees is like 2060. Four degrees is 2075. And five degrees up is 2100. That’s in the not too distant future.”

It’s sounds chaotic, discordant.

“That’s a pretty cacophonous disaster,” he says.

The cacophonous disaster hits its peak in this musical composition in the year 2300, 500 years after it starts. By that time, if we’ve done nothing, the project’s climate researchers say the temperature will have risen by nine degrees Celsius, which makes that pretty melody we started with sound completely discordant -- a relentless, staticky, pounding wall of noise.

It’s hard to listen to. And that’s the point -- if the global temperatures really went up that much, the results would be catastrophic. But Walker wants people to be able to stay with the bigger point of the piece… that we’re not there yet. That it doesn’t have to be inevitable.

“So periodically during this cacophony as things get wilder and wilder, we pause, and we refer back to where the world would be if we managed to hold it at two degrees,” he says. “Because that's where we need to be able to hold it. That would be … liveable. So that gives us a ray of hope in this.”

This piece first aired on May 31, 2016.

The Bay Area The Climate Music Project will perform Erik Ian Walker's work as part of a show this Friday April 28th at NOHSpace in San Francisco's Mission District.