Eighteen-year-old Milton* knows all the songs on the radio, even if he can’t pronounce all the words in English. He’s singing along with Christian Ruiz, who along with being his soccer coach and friend, is also Milton's mentor in a million ways, even though at 21 he's just three years older.

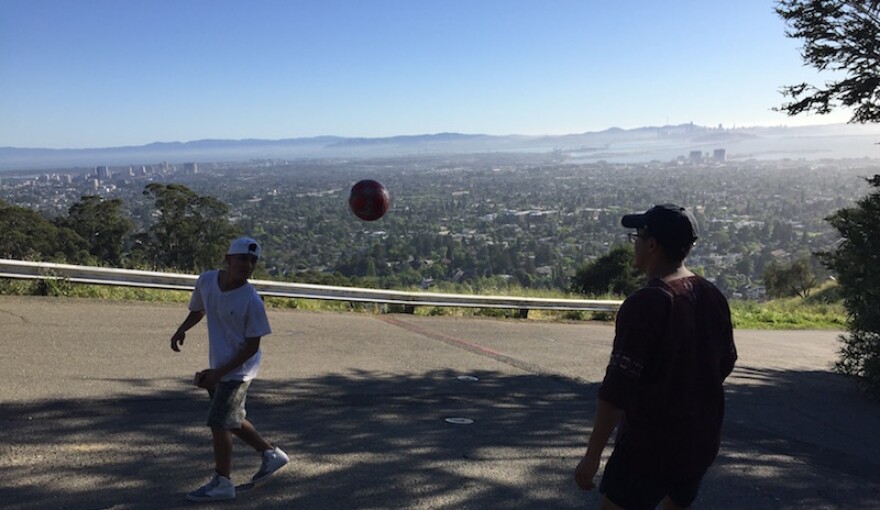

I’m riding along as Christian takes Milton up to the Berkeley Hills, just for the view. He’s been showing him around the Bay Area since Milton first arrived a little over a year ago.

Milton is captain of his soccer team, and he also has a reputation for being a class clown. The whole ride up he’s telling dramatic stories about why he hasn’t done his homework.

As soon as we’re out of the car, Milton’s running ahead with a soccer ball. Oakland and Berkeley bake in the hot haze below us. I pant, climbing up a slope, while Milton dribbles the soccer ball in circles around me doing tricks.

Milton came here from Guatemala. His mom has medical bills and he says in his village there was no way for him to scrape up the money to pay them. So, like so many young migrants, he came here to work.

At the top of the hill Milton squints, and makes out the Fruitvale neighborhood, where he’s lived for most of his time in the Bay Area. He points out the tree-lined streets of Elmwood, where he just moved.

Milton was just 15 when he came to this country. He lived in Florida for just under a year and worked full time. There, and then in Oakland, he bounced around different relatives’ and friends' houses. When his housing became stable enough, Milton enrolled in school. When that house got too crowded -- with 13 people living in two rooms -- he started sleeping on the floor at a friend’s place. That’s where Christian dropped him off after soccer practice.

“He’s looking at the place and he said ‘Ah bro, it's hella bad,’ Milton remembers, “He said, ‘no, bro, why you didn’t tell me?’”

Christian knew Milton couldn’t keep living where he was, but he couldn’t let him drop out of school. That would mean giving up his social life, the soccer team, and the opportunity to have a real career.

“He was having a bit of a breakdown and freaking out,” says Christian.

Together, these two young men tried to figure out Milton’s options.

“I find a way because Christian,” says Milton. “I told him what happened to me and he said, ‘I can help you.’”

Even though unaccompanied minors are at much higher risk of homelessness than citizens, it’s a lot harder for them to get help. If children who are born in this country aren't properly housed or cared for by adults in their lives, they'll often go into foster care. Kids like Milton, who don’t have green cards, don't have access to such services.

Only one shelter in Oakland takes minors for temporary stays. They say the number of migrant children coming to them has been growing, an estimated 35 minors in the last four months. Staff at this shelter were reticent to talk to me. They said it was unwise to be identified with undocumented services, given the politics of federal funding right now.

There’s also only one long-term housing support program in the Bay Area for unaccompanied minors, the Refugee Foster Care Program from Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County. That program can only support youth who've won asylum status —which fortunately, Milton had. This was his one shot for getting stable housing without giving up the life he’d made here, but he was turning 18 soon, at which point he’d no longer qualify for help. The process was moving really slowly.

“He would text me or call me in the moments,” says Christian, “I could feel like he was about to cry... just really hard moments where there was no one else.”

On the phone, Milton's mother was telling him to stay in school, but Milton felt his whole reason for being in the US was to help her financially. Then, four days before his 18th birthday, he got into the long-term housing program he applied to.

Milton moved into a spare bedroom in a classic, brown-shingle, Berkeley house on a block full of near-mansions and immaculate gardens. He shares the house with one man, who doesn’t have custody of Milton, but did get vetted by the program.

“The house is big. You got a kitchen, you got a bed, you got a big room,” says Milton. “It’s good for me. I’m excited.”

Milton beat the odds. Though he still works to send money back to Guatemala, he can do that after school and on the weekends. With rent covered, he gets to keep being a teenager. His cousins came here a few years before and they weren’t as lucky.

“They’re working. They’re not going to school because they need to help the families,” says Milton.

He says his cousins have lived isolated lives ever since they came to this country, and moved in with a distant relative that could only house them long enough to find work and move out.

“They live lonely,” says Milton. “Nobody told them that school’s good, you need to go into school. Nobody.”

Nobody's looking after them, he says. Immigration enforcement releases young migrants into the custody of an adult sponsor, but rarely checks back up on them. Many minor migrants end up fending for themselves.

All of Milton’s soccer teammates are new to this country. It’s a league for recent immigrants. I ask him how many he thinks are in a position like he was, living in conditions so bad they might have to drop out of school in order to scrape up the money to live somewhere better.

He and Christian put their heads together and count four other players. What’s harder to measure are the housing needs of the young people who aren’t in school and aren’t connected to adults like Christian. We can only guess at that population, but we know that out of all the kids who enroll in Oakland schools when they first come to this country, about a quarter drop out.

Sergio Medina has worked in child refugee services for 18 years. In the past he ran a shelter in the East Bay and now he runs an organization called RISE -- Refugee and Immigrant Services.

“The missing part is the size of the problem. We just don't know how many undocumented kids are alone,” he says.

Medina has heard stories like Milton’s countless times. He says so many of the living arrangements between unaccompanied kids and their sponsors are like ticking time bombs.

“Resentment in the family kind of builds,” says Medina. “Like, ‘Oh, we’re helping out this kid, what about our children? You’re helping your third cousin twice removed.’ So, then the kid feels really uncomfortable and says ‘I'm not welcome here.’”

“Then it can get much worse,” says Medina. “Scenarios can and do get much worse.”

Medina says when a kid is taken in by a sponsor who's not close family, there are often strings attached. The deal can easily verge on exploitation. This wasn’t Milton’s experience, but Medina says there are adult sponsors out there who take advantage of the situation. It’s part of the broad spectrum that is child trafficking.

Medina’s met a lot of young migrants that stay with exploitative sponsors because they have no other option. For example, he tells me about two teenage girls he knew who were living with a man unrelated to him. The man was forcing them to have sex in exchange for rent and food.

Medina says he tried to persuade them to come to the shelter and apply for transitional housing. One of them chose to stay in the man’s house, and the other escaped on her own.

Medina says for kids who do depart, “They leave into the unknown. We can’t underestimate how difficult that decision is to make.”

Every young person that’s made it to this country on their own has already made at least one impossibly difficult decision -- to leave home.

As for 18-year-old Milton, he says it’s been a lot harder here than he pictured.

“If you don't have family here it's very difficult for live because you need to find a job, pay the rent, phone, food, everything,” says Milton.

In the really lonely moments, he says he regrets coming.

“Sometimes because I miss my family. When I call my mom she says ‘When you come back to Guatemala?” and I say ‘tomorrow’ and she says ‘what?’”

It’s a fantasy that ends as soon as the words are out. Milton says she can’t help asking. “She feels bad," he says, "but she’s sick and needs money and that’s why I’m working.”

That’s why he came here — In a way, to keep his family from falling apart. But with his asylum status, he can’t go back; they may never be together again. So, for Milton and the many unaccompanied migrant youth living here, it’s the only way forward.