When someone is imprisoned, it doesn’t just affect the incarcerated. It affects the people left behind. Young people. Nearly three million children in the united states have parents in the criminal justice system – it’s almost 1 in 10 kids in California alone. It can be costly and difficult to visit or call a parent behind bars. And losing a relationship can be traumatic... with lasting consequences. A new art exhibit on Alcatraz Islan, called The Sentence Unseen, examines this reality. KALW’s Catherine Girardeau has the story.

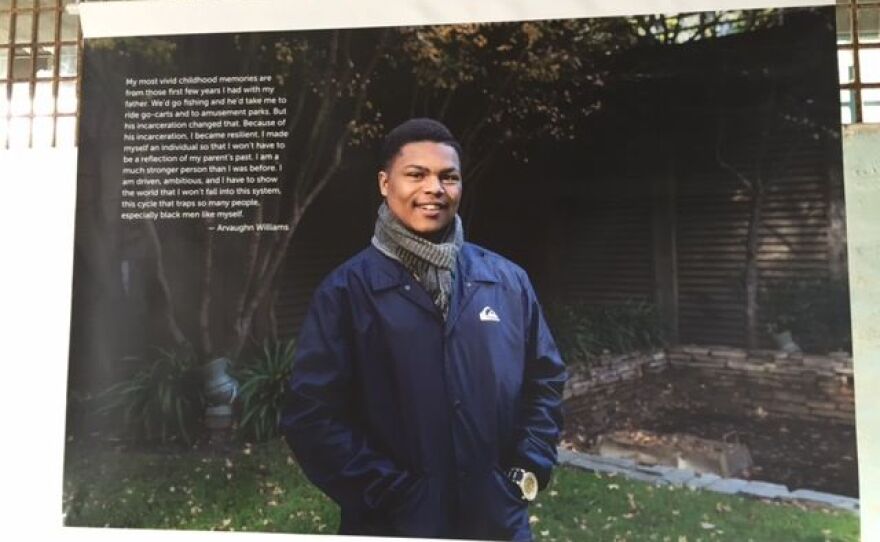

Sixteen-year-old Arvaughn Williams is one of the youth artists. Standing beside a big, glossy photograph of himself standing in a garden – smiling and confident, with a plaid scarf stylishly tied at his neck – he reads his quote below the photo.

"My most vivid childhood memories are those I had with my father," he says. "We'd go fishing, and he'd take me on go-cart rides and to amusement parks. But his incarceration changed that. Because of his incarceration, I became resilient. I have to show the world that I won't fall into this system and this cycle that traps so many people, black men like myself."

Williams is a junior at City Arts and Technology High School in San Francisco and a youth advocate with Project WHAT! The program raises awareness about what it means to live with a parent in prison. He says he had only intermittent contact with his dad after the age of 5. The WHAT in Project WHAT! stands for “We’re Here and Talking,” and Williams talks about one very important conversation three years ago, shortly before his dad passed away.

"I had told him that it was hard growing up without him there," Williams says. "Like I had to learn how to shave on my own, I had to learn how to do things on my own, which sometimes led to me going down the wrong path. And I told him that he could have curbed all that if his presence was just within the household."

Although the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation doesn’t track the number of inmates who are parents, studies estimate that nearly 1 in 10 California children have a parent in the criminal justice system. Public health studies show that, for kids, having an incarcerated parent is associated with a high level of childhood trauma. So Project WHAT! put together a set of policy recommendations for the County of San Francisco that aims to make things a little easier for kids with parents behind bars.

Prison visits difficult

Family visits can help alleviate some of the stress, but those visits can be infrequent and hard to organize. Prisoners are frequently housed far from home, and some families can’t afford the travel costs to visit their loved ones.

Sixteen-year-old Oakland resident Xitlally Lupian’s dad was incarcerated when she was just eight months old. In the years since, he’s been transferred at least five times. Standing in front of her portrait, the soft-spoken young woman with brilliant maroon hair tells me about her dad’s most recent move.

"I visited him like two weeks ago for the first time in like three years," she says, "because my family doesn't have all the money to be going there every two weeks or even once a month."

Lupian says her dad was previously in Folsom, about a two-hour drive from her home. But then he was moved.

"No one told me that he got transferred," she says. "I didn't know until he sent a letter and the stamp said Pelican Bay State Prison. I was like, 'Where is that?'"

Lupian later found out Pelican Bay State Prison was in Crescent City, more than 350 miles north of the Bay Area. One of Project WHAT!’s policy recommendations is for the city of San Francisco to provide travel funding to families to cover the child’s transportation costs for a minimum of six visits per year. While there are some limited free bus services to some prisons, families generally have to figure it out on their own, carpooling and sharing costs. And when they get there, the visit may not go as planned, as Lupian explains.

"I had to see him behind the glass, through the window like with the phone," she says. "And it was only three hours."

Lupian says she wasn’t able to hug, touch, or even hear her dad very well on that last visit, but what she did hear meant a lot to her.

"I almost started crying, because he told me that he really loved me, and that, like, he had never loved anybody as much as he loved me," she says. "Then he started talking to my mom and she said, 'Oh, she's such an amazing daughter!' and all that and I think all three of us – me, my mom and my grandma – started crying."

Lupian’s father has been present for some important moments in her life. She took her first steps during a visit to Corcoran State Prison when she was a year old. But that’s luck – incarcerated parents usually aren’t there to witness their kids’ milestones. Project WHAT! alumnus and youth advocate Tony Shavers says that’s part of what the group is trying to change.

"We go up to Sacramento, we lobby in front of state legislators, policy directors, to really get them thinking about what policies and what changes need to go into effect to really help children," Shavers says.

When parents are released, families need support

There are some parts of incarceration that are harder for policies to address – feelings of disappointment, abandonment, and loss. To address some of this, the help Project WHAT! is advocating for includes family counseling support services when parents are released.

One family's story shows just how difficult that re-entry process can be. Joe Calderon was released from prison four years ago. He was at Alcatraz with his family, including daughter Jessica, a youth advocate with Project WHAT, and talks about what it was like trying to maintain a relationship with her.

"Jessica was born when I was in County Jail," he says. "I got to see and hold her one time before I went to prison."

Calderon says he wrote as often as he could, sending her drawings and birthday cards to let her know who he was and how much he cared about her. But when Calderon came home after 17 years in prison, it was the first time he’d lived in the same household with his daughter. Jessica says it was a new phase of their relationship.

"When he was incarcerated I feel like we had a good relationship, but that's basing it off of like visiting him maybe every other month, and almost kind of being like distant relatives," she says.

Now that her dad is home, Jessica says their relationship is sometimes tough.

"There's things I'm not used to," she explains. "He's very old school, and that’s the way he was raised and I wasn’t so much raised that way. Obviously there's still sort of a prison mentality sometimes."

For his part, Joe Calderon says he’s turned his life around. He works for the transitions clinic on the San Francisco Re-entry Council, helping former inmates integrate back into life on the outside. And, he says, he has made the decision to put his family first.

His daughter Jessica tries to stay focused on the present, rather than the past, but sometimes it’s hard. She says she's still a little bit resentful sometimes, but overall, she's hopeful she and her father can rebuild a bond. She says it would help to feel like she didn’t have to do that work on her own.

"I think it's very important that children, before their parents come back, there's that counseling and there’s that talk about what the family dynamic will look like," she says. "What's working, what's not working, how can we make it work?"

Providing family support services is just one of the policies Project WHAT! hopes to have passed. Four of their recommendations have already been approved by the San Francisco Police Commission or the San Francisco Sheriff:

1. a. All SF Police Department officers should be trained and required to follow protocol regarding children of incarcerated parents on how to reduce trauma to children when arresting a parent.

1. b. The SF Sheriff’s Department should make their “inmate locator” user friendly and accessible online so that children and youth can find out where their parent is located and how to contact them.

2. a. When youth are 16 years old they should be able to visit their parents by themselves in SF County Jail without another parent or guardian present for their visit (which is consistent with the Federal Prison System’s visiting age.)

2. b. When a parent is transferred from SF county jail to the CA state prison system, children should be offered three private contact visits to say good-bye to their parent, known as "Good bye visits".

The group hopes to get the next six recommendations passed as well.

You can see “The Sentence Unseen: Portraits of Resilience” on Alcatraz through August 31st – click here for tickets. Or catch the exhibition at Oakland’s African American Museum and Library beginning in October.