Bay Area homes, businesses, and factories send about 550 million gallons of wastewater to treatment plants every day. That’s enough water to fill 750 Olympic-sized swimming pools. Just six percent of this water gets re-used for agricultural, industrial, and other non-potable purposes – meaning nobody drinks it. The rest gets discharged back into the Bay.

But there is a way Bay Area residents could reuse all of that water – even for drinking. Right now, a new water purification plant in Alviso, part of San Jose, is producing water experts say is drinkable. But are residents ready to swallow it?

The purification process

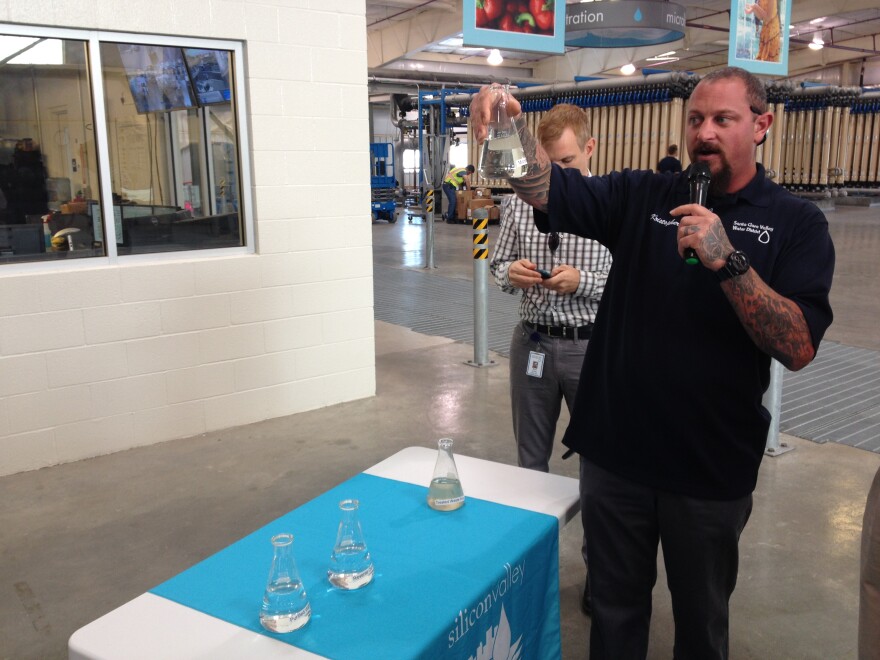

I am on a tour of the new Silicon Valley Advanced Water Purification Center and I’m surrounded by shiny tanks, chugging pumps, and pipelines painted blue, yellow, and green. There is a lot of noise, too. Machines are roaring all around me.

My guide is plant operator, Kristopher Filice. He starts at the beginning.

“If you look in that direction over there, those pumps are what bring water into the plant,” Filice points out.

The water comes from a nearby waste treatment facility. That means it has already been purified a little bit. But it’s about to embark on a journey, the likes of which no water molecule in the Bay Area has ever seen. At least not since this plant opened earlier this summer. It starts with a first level of filtration.

“So when the water comes into the plant, it actually comes through auto strainers. These are just a strainer basket,” Filice explains. “It's just to catch the big stuff – [like] birds. I mean there's all kinds of stuff that comes in from the other side.”

Someone in my tour group – I’m not alone here – just asked Filice what’s the coolest thing he’s found in the water intake filters.

“I try not to open those ever,” says Filice, “I try to stay as far away from that stuff as possible.”

After this “bird” level of filtration, the water moves on to much finer levels, passing through pores 300 times thinner than a strand of hair. Next, it’s on to a process called reverse osmosis. This removes unwanted stuff at the molecular level.

Filice explains it this way: “All you're doing is making enough pressure to push a bunch of water through an expensive piece of paper. It comes out clean on one side. It's dirty on the other.”

According to Filice, at this point, the water is “really clean.”

The last step – Ultraviolet light filtration – breaks deals with any viruses that may be in the water.

“We can not actually kill a virus. But you kill its ability to reproduce,” says Filice. “They don’t live long at all.”

After all this purification, this water sounds like it should be clean enough to drink. But Filice says he’s not ready to drink it yet.

“It's still not regulated by the Health department,” he says. “It hasn't been cleared to drink. I haven't gotten mentally over it yet. I mean, mentally, it's coming from the toilet to tap.”

Getting over toilet-to-tap

The toilet-to-tap stigma is a big obstacle. Right now there’s only one city in America where people drink recycled water directly from a plant like this -- Wichita Falls, Texas.

“We did have those in the public that said that they weren't going to drink the drinking water once we started reusing it. But they weren't going to stop us from doing it,” says Daniel Nix, operations manager for the Wichita Falls Department of Public Works.

But now, Nix says, some people actually like the recycled water better.

“When we came online, within the first day or so, the feedback we were getting was that the water quality, the taste, had actually improved,” he says. “And that was primarily due to the lowering of the salt concentration. The drought that we've been going through has concentrated those salts in our lake water, and so it's been steadily going up over three or so years.”

California is experiencing its own three-year drought. At the moment, we can’t copy Wichita Falls, because drinking recycled water is illegal here. State regulators say our laws haven’t caught up to the technology yet, but they’re working on it.

Will California embrace recycled drinking water?

At a splash park in downtown San Jose’s Plaza de Cesar Chavez, children in bathing suits run through mini geysers shooting up from the concrete.

Chris Westphal was there recently with his family. He’s happy to let his kids play in this water, and he says he’s open to drinking it, too.

“It just sounds like a good idea and we're obviously in a drought and I think anything that helps us to reuse water and be smarter about what we do with our water is a good thing so it definitely sounds like an interesting idea,” says Westphal.

A little more than half the people I talked to at the splash park felt the same way. But some, like Yen Tochimoto, weren’t so sure.

“If the water doesn't come from a natural source, or it's been used for something else, it doesn't give you that impression of being clean,” Tochimoto told me.

From reject to reuse

Frankly, on the plant tour, there are points where I don’t get the impression that this water could be clean again. Like when we come to the deep concrete pit full of all the stuff that gets rejected from the plant. I peek over the edge with fellow visitor, Brayton McKnight.

“It doesn't look good. It's brown, foamy, not something you'd want to drink, for sure,” says McKnight. “Frothy. That's a good word for it.”

And yet McKnight says that now, after the tour, he’d drink the water from this plant.

“Yeah definitely,” he says. “I didn't know a whole lot before so I probably wouldn't have known what to say.”

Officials with the city of San Jose know what they’d say. The Mayor and the Department of the Environment have stated that they want to incorporate the water from this plant into the drinking system as soon as possible.

But until state policy changes, the water from the Silicon Valley Advanced Water Purification Center will get sold for reuse in fountains and irrigation systems around the South Bay.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the water from the Silicon Valley Advanced Water Purification Center would get pumped out into the Bay. It also incorrectly stated that the same water was used in San Jose's Plaza de Cesar Chavez fountains. Both references have been removed from the print version of this story, but remain in the audio.